Stop Grading Essays, Start Grading Chats

An Introduction to a new method for assessing student thinking in the age of AI

Today, I'm excited to share a novel method of student evaluation that I implemented four separate times during the ‘23-24 school year. Despite its limited trials, this method has provided meaningful insights into how teachers can continue to develop critical thinking in their students in the age of AI by placing themselves within the “process” of learning rather than primarily evaluating the “outputs” of our traditional assessments.

Disclaimer: Before diving in, I’d like to to note that this framework does assume some familiarity with AI. However, it is also crafted to enhance AI literacy. Even if you are a novice AI user, engaging with this method will naturally bolster your understanding and comfort with AI technologies.

I sincerely hope this approach will gain traction in high schools and colleges. Other AI-in-education pioneers like Nick Potkalitsky have been writing or discussing the concept of focusing on “process over product” for some time now. Still others, like Jack Dougall and some university professors, have begun including “reflections” after using AI to create some stickiness to the process of developing AI Literacy in students.

I agree wholeheartedly with both. However, it is not enough to redesign our assessment frameworks in piecemeal fashion. It needs to be wholesale, and furthermore, it is also time to fundamentally reevaluate our roles in the classroom. If AI can (supposedly) replace so many functions of a classroom or university teacher, then what exactly is our new role in the learning process? This method, I hope, helps to move forward the process of redefining our contributions to student learning. It isn't just about adapting to AI; it's about reinforcing our value in guiding critical and creative thinking.

Introduction:

As a framework, The Kentz Assessment Method © includes preparation activities to kickstart student thinking before AI use, mechanisms for developing AI Literacy, evaluation windows for assessing content-specific understandings within the context of AI usage, and a reflective assessment that stresses the importance of critically reviewing AI-generated content. Moreover, it fosters a form of meta-cognitive and creative thinking that I once only dreamed of developing in my classroom.

I first used this concept in September of 2023 but have since tweaked and added a few pieces – like the “Purpose Statement” and the “What-Why-How” approach. I invite feedback via the comments section, LinkedIn, or through direct message here on Substack. Most of all though, I look forward to future collaborations with any interested educators!

Framework:

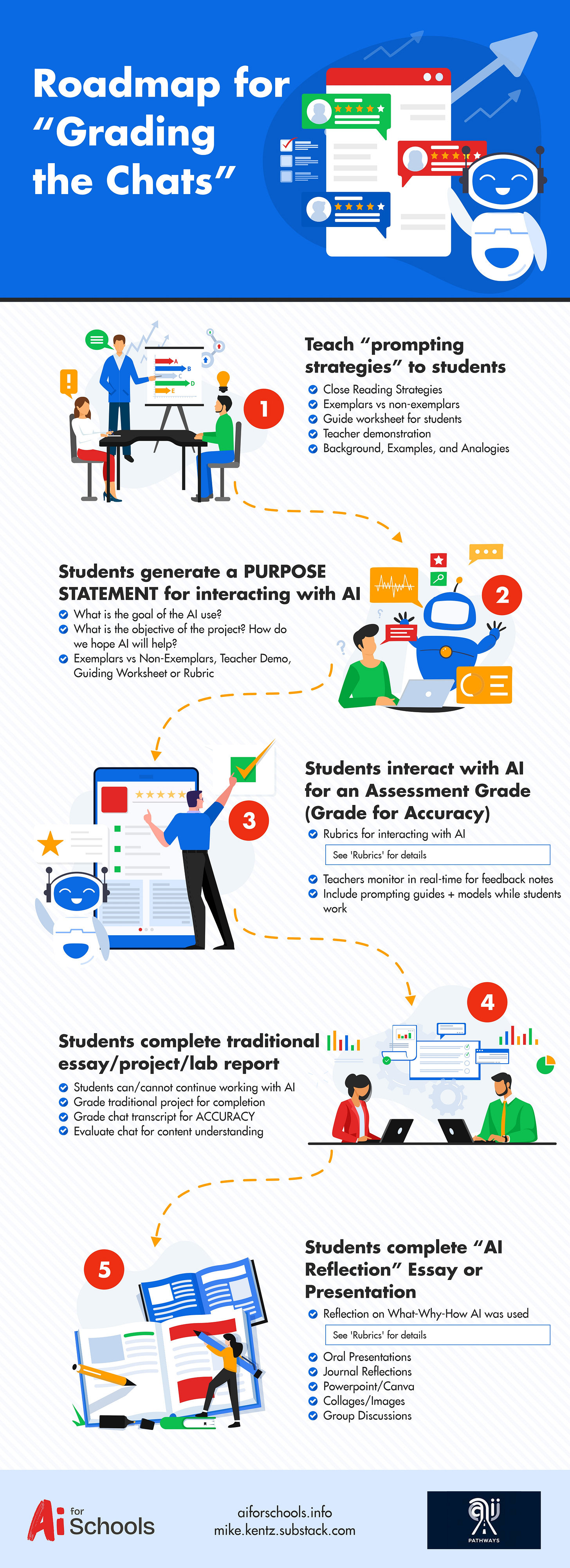

STEP 1: Teach Prompting Strategies

The first step is for the teacher to dictate the terms of a healthy interaction with AI. A year ago, this was called “prompt engineering.” Today, that concept has evolved and been re-shaped in ways that sometimes escape articulation.

For the purposes of my framework, I will refer to “teaching healthy interactions with AI” as “prompting strategies.” You can also refer to the below “Principles for Effective AI Use” as a set of grounding parameters.

”Prompting strategies” also includes demonstrating the process of iteration alongside the methods for drawing up effective initial prompts. Acronyms and names like ‘Role Construction Approach’ are all sticky ways to give your students a starting point, but I believe we have to go further.

Teachers can and should demonstrate the value of effective prompting strategies by applying close reading strategies to chat transcripts during this initial phase. For example, teachers should ask their students to read and annotate multiple chats against a rubric or set of guiding questions. They can develop classroom debates around the efficacy of different strategies, or ask for “repeat readings” with a different set of guided questions to take understanding to deeper levels. Even graphic organizers can be utilized to develop AI Literacy in this way.

Case Study: In February of 2024 I designed a project-based learning exercise after reading Romeo and Juliet in which my students would be required to use ChatGPT as a brainstorm partner. I told them I would grade their chats against a provided rubric.

I was teaching prompting strategies using the acronyms and approaches that I learned from taking a Prompt Engineering Course through Coursera and scouring the Internet for student-friendly approaches. But still, my students weren’t getting it.

So I gave them two chat transcripts which I had generated on my own — one “good” and one “bad.” I didn't reveal which was the “exemplar” and which was the “non-exemplar,” but instead asked them to evaluate both against our rubric. I included a set of guiding questions, one of which was “Is prompting even a skill?” This type of open-ended question increased freedom of thought and allowed the students to draw their own conclusions.

This close reading strategy was by far the most effective that I have used in my attempts to teach AI Literacy. I saw the lightbulb go off in many of their heads. They nodded reflexively and sat back in their chairs.

To be sure, it did not cover every base; I couldn’t suddenly call them “AI experts.” But I could confidently ask them to work with ChatGPT with the rubric we had used in the close reading activity as a guide and grade their chats, even if some of the details were still fuzzy.

From there, we ventured into the project as collaborators. They understood that I might not be able to answer every one of their questions about grading execution, but they appreciated both the collaborative trust I was placing in them and the opportunity to engage in a novel learning experience.

I told them that I would ultimately be fair when grading their interaction, but I needed them to show me some effort. From there, we wandered into unknown territory as partners working within the framework of a mutual understanding.

Step Two: Students Generate an “AI Purpose Statement”

Each assignment's purpose will differ. The teacher must guide students in crafting a purpose statement that defines what they aim to achieve by using AI and how they plan to do it. Interestingly, both teacher and student need to engage in this process separately.

On the teacher side, we can use handy items like Leon Furze’s AI Assessment Scale to first ask ourselves questions like; “For which part of the project do I want them to use AI? Why? If that is the case, how could my student go about trying to reach that goal?”

This planning process actually mirrors the What-Why-How approach that students will engage with in the reflection part of this framework (Step Five). The purpose statement portion forces both teacher and student to get clear on what they actually want to achieve by using AI, why they want to achieve that particular goal, and how they plan to go about achieving it.

Once the teacher is clear on their own what, why, and how, they must guide students in determining their purpose for using AI, within the parameters outlined by the teacher.

Side note: I have created teacher guides, rubrics, and student-facing materials for each one of these sections and will be to releasing them for free to any interested educators. Stay tuned!

Case Study: When I designed this Catcher in the Rye project, I had to be thoughtful about the purpose. Holden could not, of course, help my students with writing an essay or creating a presentation. Nor could he analyze J.D. Salinger’s choices in writing the story. But he could answer questions about himself and key moments from his own story…maybe. Thus, the goal would center around the specific bot’s capabilities.

I laid out to my students that their goal should be to answer many of the unanswered questions from the story. Because Holden is depressed and borderline suicidal, achieving this goal would require active listening, empathy, and patience. Therefore and thus, these factors shaped our over-arching purpose and methods for achieving it.

As a result, the next step of the project was to generate interview questions that a) focused on the unanswered bugbears of the story, b) took into account Holden’s emotional state and triggers, and c) were open-ended in nature so that “HoldenAI” could take the conversation where he wanted to go — a strategy I taught my students that would possibly make “him” more comfortable.

In that case, my student’s interview questions were essentially their purpose statements. It was later in the year that I added this section to the framework.

On the flip side, if you decide to have your students use ChatGPT as a brainstorm partner, the objective and purpose might center around generating a handful of ideas about mode, method, and content of a project or presentation – and then narrowing down within the chat itself to one particular route that the student can articulate and justify.

The key point is that the teacher must guide this process fairly closely, at least at the beginning. Over time, students are likely to become more comfortable with this process and intuitively generate purpose statements with much less guidance. But for now, we have to create pre-engagement exercises that help our students be thoughtful before they even start to use the technology.

Step Three: Students Interact with AI for an Assessment Grade

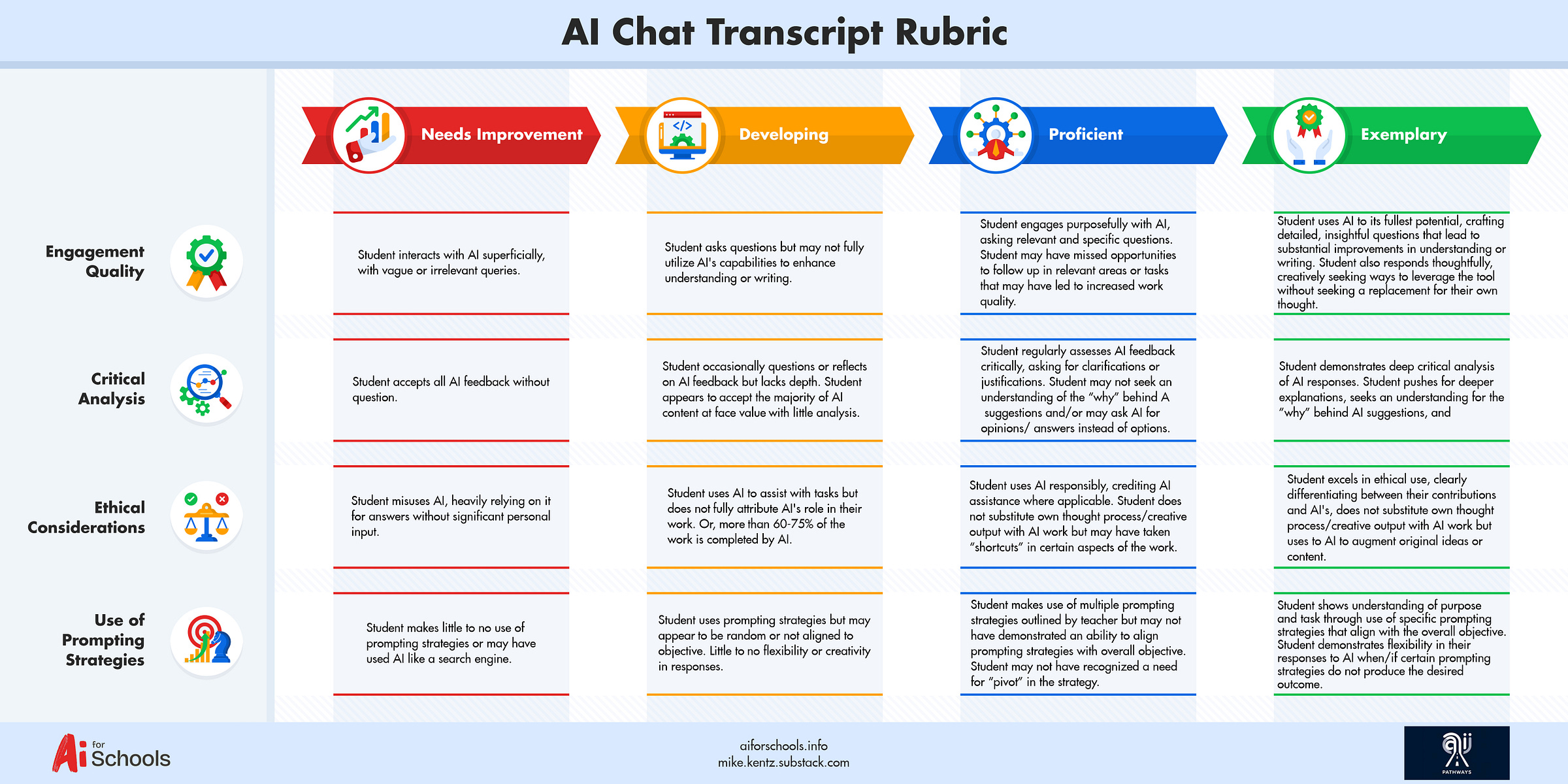

For this step, rubrics are your best friend. Before students engage with the bot for the graded chat, teachers should provide time for student analysis of rubric. Ideally, this would occur during the close reading section from step one. If not, students should have some time to digest and ask questions about the goals you have outlined.

Below is a boilerplate rubric that can be adjusted for subject, task, activity, and/or objective. As you roll yours out, you can provide guided questions, ask students to analyze the document in groups, or engage in a step-by-step teacher walkthrough

Then, students are ready to engage with the bot of your choosing for a grade. Below are two clarifying questions that I often hear when I outline this approach to fellow teachers, along with my hopefully sufficient responses.

#1: When and where does this interaction occur? In class? At home? How long should I give them to work with the bot? What if they transcript ends up being 100 pages?

The easy answer is “it’s up to you.” But were I to provide guidance based on my experience, I would say you can execute this in one of two ways:

1) Give a time limit in class: For example, students have thirty minutes to use AI while working on their project and then they have to submit their chat. Or, if you are using platforms like SchoolAI, MagicSchoolAI, or Khanmigo’s Writing Assistant, you have automatic monitoring access and can use time stamps to “cut them off” for your assessment. These tools also allow you to provide in-the-moment feedback if you see a student going “off the rails” and want to nudge them back on track.

2) Give them a question limit: For one experiment, I told my students they could only ask five questions for the assessment itself. I knew I couldn’t stop them from using AI afterward, so I told them that yes, they could continue using it after the allotted amount. But for those five questions, I had better see evidence of the categories I named on the rubric. As a result, my students had to be hyper-focused on their prompts and iterations in order to receive a passing grade on an activity that became a major portion of the assessment.

#2: What if my students have never used AI?

Great question. Either way, for your first iteration of this project, I would give them a “dry run.” Allow them to work with the bot of your choosing with the rubric and/or guiding materials in tow without grading the chat. Or, monitor and grade it for effort or as a homework or “lesser value” assignment. The goal here is to give them some time to feel familiar with the technology.

Case Study: Before I required my students to use ChatGPT as a brainstorm partner, I first had them generate a list of “Bucket List Items” and/or Life Goals they have always wanted to achieve. Then I allowed/asked them to use ChatGPT to develop a plan to achieve that goal or knock the item off their list using the strategies and rubrics I had provided.

In this case, I did grade their chats, but only as a homework assignment. The reduced value and understanding that this was a practice run lowered the stress level for anyone involved while giving them a chance to practice some innovative skills and get feedback.

To be fair, it was a heavy lift on my end. But my thinking was (and remains) that the requirement for a “dry run” will slowly disappear over time as students become familiar with the approach itself, your rubrics, and the capabilities of specific bots. Within the context of these “early days” though, I thought of it as a way to provide a trial round of feedback before “The Big Game.”

Step Four: (Optional) Students complete traditional essay/lab report/project

This step is tricky. In some cases, like my Holden project, I was able to skip right from the chat itself to Step Five (the reflection) and create an essay prompt that forced my students to embed content understandings about character, theme, and book alongside their analysis of the AI bot – all in one fell swoop. It essentially combined Step Four and Step Five.

For other projects, like my ChatGPT-assisted one, I could not achieve that goal with one essay or project prompt and had to ask them to complete a “main project” that followed traditional guidelines.

In that case, the beauty was that I did not need to execute a line-by-line evaluation of their traditional outputs. (Some were essays, some were videos, some were presentations.) I was able to access much of their thinking and development of ideas from the initial chat itself.

And, since I knew they were heavily using AI after the initial chat, I asked them to verbally present their main presentation to the class at the end rather than simply handing it in for my analysis. By focusing my grading efforts on their ability to articulate the thrust of their project rather than the content itself, I avoided that frustrating “AI cheating” issue — while still operating within the confines of a traditional project output.

This is sometimes where I lose people. Keep in mind, in a matter of years, it is possible if not likely that nearly all writing will be AI-assisted. Most if not all students will likely be using it at home whether we like it or not.

As such, it is more important to develop AI Literacy skills now than it is to hold on to our traditional assessments. Students can still complete traditional literary analysis essays, lab reports, or presentations, we just need to grade them differently.

The more we emphasize a thoughtful approach to AI interactions and provide thoughtful feedback, the more our students will come to understand how to develop and maintain a healthy relationship with the technology.

They will be able to resist the temptation to ask AI to do work for them, and instead learn how to leverage AI to do better work.

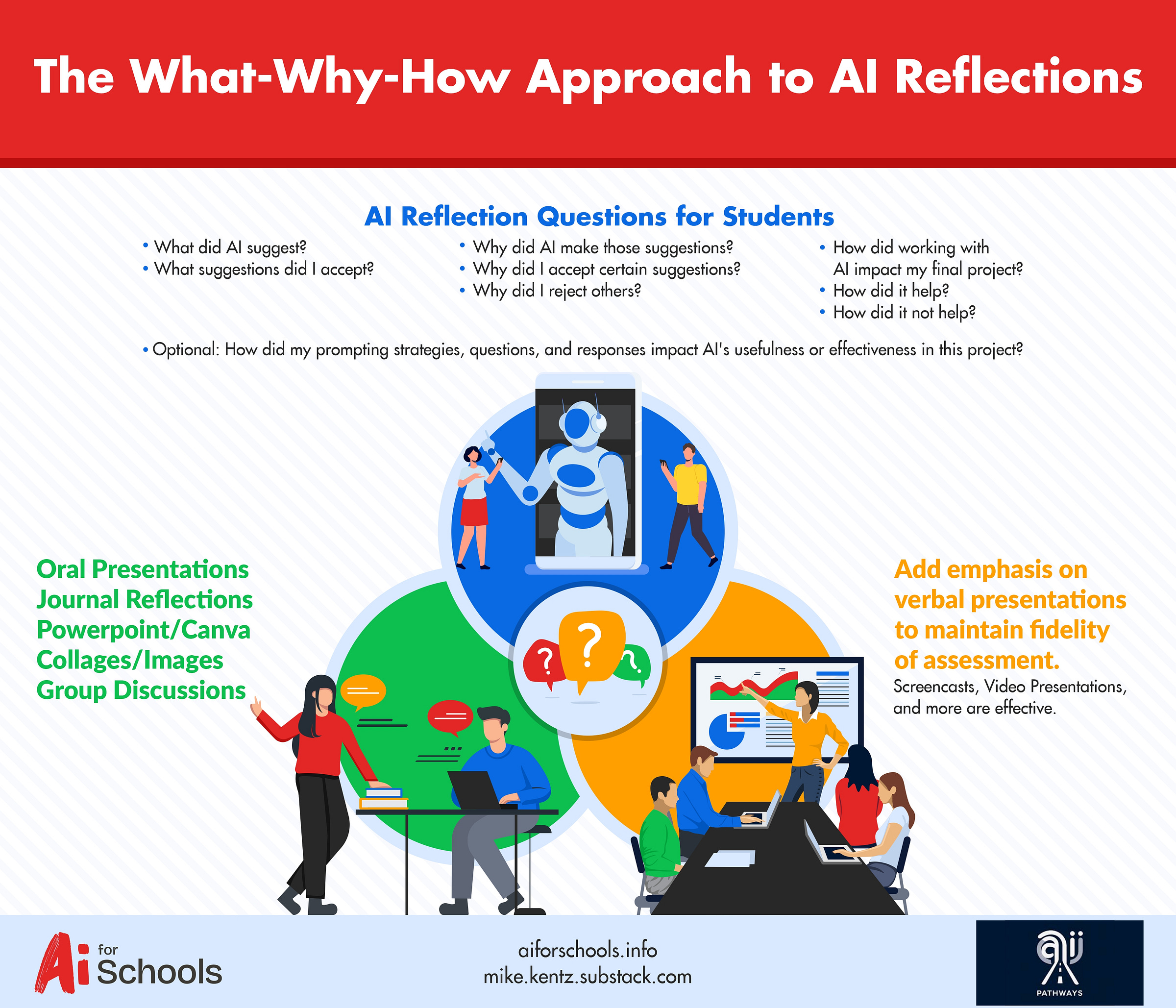

Step 5: AI Reflection

This is my favorite part. In this section, students complete a journal, presentation, screencast, collage, short essay – whatever you choose, really – that reflects on their use of AI.

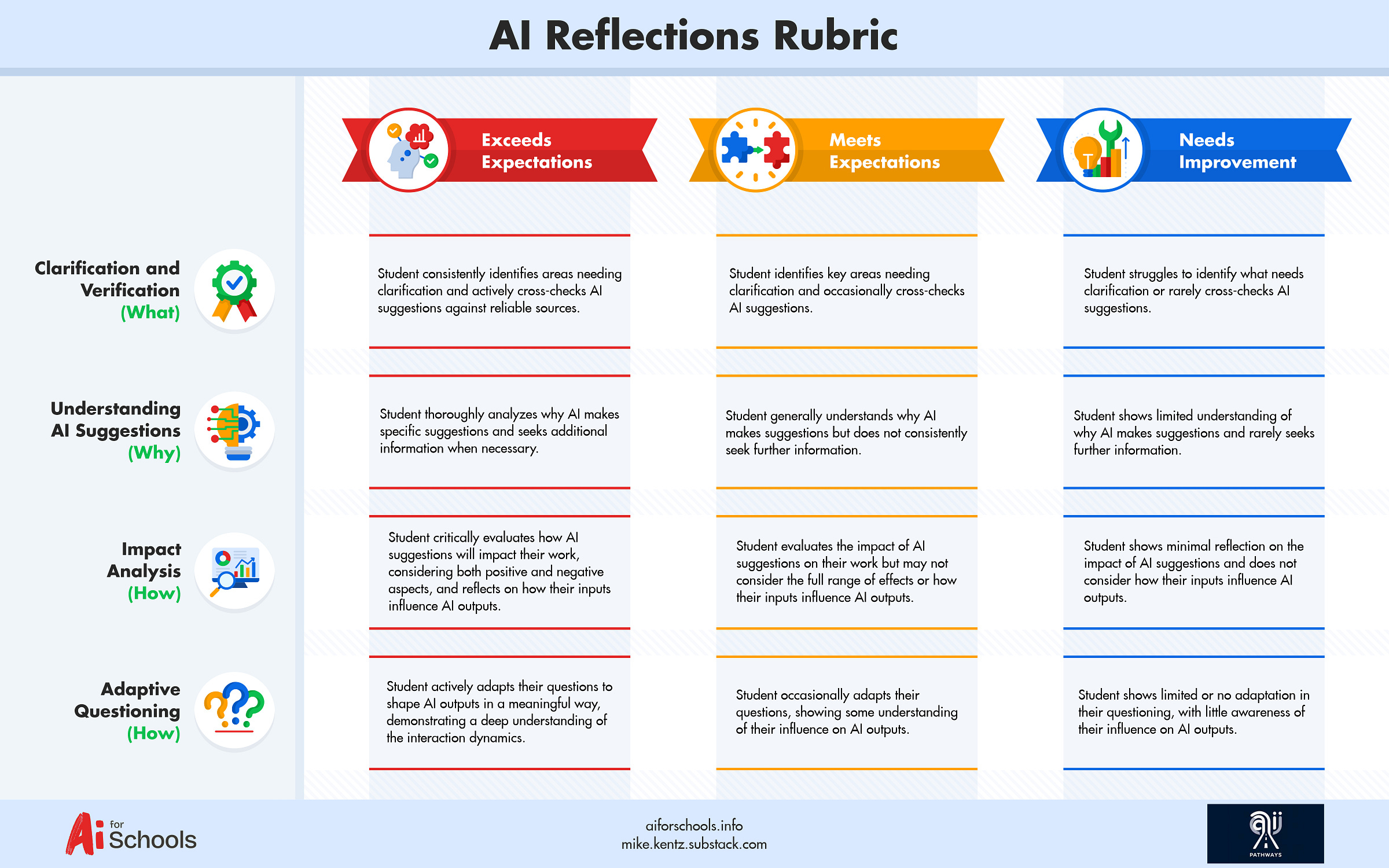

To complete this, students use the “What-Why-How Approach” that I began to outline earlier in this piece.

The beauty of this approach is that – in order to meet the learning goals -- students have to ask AI why it is making the suggestions it is making. What could be better than that?! Students must continuously evaluate what AI is producing, why it is producing that particular content or suggestion, and how it is impacting their overall work.

This process leads to perhaps the important lesson that teachers can embed and emphasize through the entire course of the project framework:

It is a good idea to always — or often — ask AI “why” it is offering the suggestions or changes that it offers.

Even if students “forget” to ask in the initial transcript or in the moment, they can either a) go back and pull up an old response and ask AI for further analysis or b) generate their own analysis as to “what AI was thinking” on their own. Super meta-cognitive!

To be fair, your students might find it exhausting to ask “why” on every single prompt. The truth is they do not have to — but they should be asking it some of the time. I think you will find even that is plenty and still a win.

I do not have space to share case studies for this portion of the project, but I will be sharing more in the coming months, including the essay prompt and student outputs from my first experiment.

Here is another boilerplate rubric I believe can be used in SY ’24-25. This can and should be adjusted depending on the context of your project.

Conclusion

My goal in putting out this approach is to invite feedback and start down a pathway of research, development, and refinement. While I recognize that it is not fully tested and is likely to have unseen flaws, I do believe that the concept and some of the specifics have the ability to stand the test of time. The core of this framework will remain useful and relevant, I believe, even as AI tools improve.

Lastly, I plan to organize a cohort of educators for the Fall of 2024 that are interested in experimenting with it in their classrooms.

If you are interested, please DM me on Substack or reach out on LinkedIn!

I will also be presenting this framework five times this summer:

1) Learning Ideas Conference (June 14, NYC)

2) Course Hero Education Summit (June 20, Online)

3) AI for Education Webinar (July 18, Online)

4) Teaching and Learning with AI (Orlando, July 24)

5) TCEA AI for Educators Conference (July 25, Online)

I hope you can join!

In the meantime, I’d ask you to consider whether or not this approach reflects the real role of the teacher in the future. Is this now our purpose? I believe so. What do you think?

This is incredible, Mike. Truly!!! You are working on the bleeding edge here. Let me know how I can assist in getting the word out.

This framework seems great. I'm excited to give it a try this school year!