Critical AI Literacy: What Is It and Why Do We Need It?

A Recent Keynote on AI Literacy and the Future of Education

Last month, I had the opportunity to deliver a keynote and two workshops for faculty and staff at Massachusetts Bay Community College’s Annual PD Day. I’m sharing the text of that speech here — edited for clarity — in the hope that these ideas can help administrators and educators deepen their own AI literacy and spark important discussions.

I’ve kept my corny warm-up jokes in because, well, I like corny jokes. I hope you enjoy them too.

Thanks for being a loyal subscriber—your engagement, support, and willingness to share these ideas keep this work going!

Good morning, everyone. I am very excited to be here in Boston to talk about AI, AI Literacy, and AI in the field of Education. I have to be honest, the last time I was in Boston was for a playoff football game in 2010 - Jets vs. Patriots. My beloved Jets won that game. We haven’t won much since, so I hold onto that memory like it’s a family heirloom. Some people pass down jewelry - but when you are a Jets fan, you pass down Mark Sanchez highlights.

I’ve been living in Savannah for the past three and a half years - winters in Georgia, summers visiting family in the Northeast. Best of both worlds. But after just two days back in Boston, I remembered why I left. I stepped outside, felt that cold wind slap me in the face, and thought, "Nope, I don’t care what my mother says, I do make good life choices."

In all seriousness, I’m here today to talk about critical AI literacy, and I am a big believer in this concept. We have to know how to use AI well in order to get the most out of it, but we also need to understand AI on a deep level to protect ourselves from the unintended consequences that come with using it.

Let me give you an example of what I mean. Last night, I was hungry, so I asked ChatGPT to find the best pizza place near me. Guess what it said? Domino’s. For real. That’s when I knew — this thing isn’t ready to replace human intelligence.

So I did what any AI-literate person would do: I shut my laptop, picked up my phone, and called a real person. That’s critical AI literacy — knowing when to trust AI and when to trust your stomach.

What Is Critical AI Literacy?

Of course, it’s more than just knowing how to spot a bad restaurant recommendation. Critical AI literacy is a skillset that involves self-reflection, awareness, analytical thinking, and more.

Let’s turn to an academic definition. Researchers at Georgia Tech (Long and Magerko, 2020) define AI literacy as “a set of competencies that enables individuals to critically evaluate AI technologies; communicate and collaborate effectively with AI; and use AI as a tool at home and in the workplace.”

Now, let’s pause for a second. That definition highlights how different our relationship with AI is compared to any other technology we’ve ever used.

AI Is Not a Toaster: Why AI Literacy Is Different

First, look at the definition—it says we need to collaborate and communicate with AI to be considered “literate.” Now, pause for a second. Think about those words: collaborate and communicate.

Do we ever talk about communicating with traditional technology? Have you ever had to collaborate with your microwave to use it effectively?

Bear with me here. I don’t know about you, but I’ve never stood in front of my oven and thought, Alright, time to collaborate. That’s just not how we interact with traditional tools. You press a button, it does its job. If it doesn’t, you call a repairman. But you certainly don’t have a back-and-forth dialogue with your oven to get it to work.

Second, think about what it means to critically evaluate a technology while using it. Now, compare that to how we interact with traditional technologies.

When have you ever needed to critically evaluate a tool in real-time? When you walk into a room and flip on a light switch, do you stop and think, I should really evaluate whether this light is working correctly? Probably not. I know I don’t. Do you?

This isn’t just an odd observation — it highlights how different our relationship with AI needs to be compared to other tools. With AI, we can’t just assume it’s working as intended. We actually have to analyze and evaluate its outputs — something we don’t do with a light bulb, a steering wheel, or an air conditioner.

From this close read analysis of the definition of AI Literacy, we can begin to see the shift that is upon us. AI is different than a lightbulb - or those other traditional technologies with which we typically interact. We actually have to assess what it’s giving us. We have to think about whether it’s making mistakes, whether it’s biased, whether it’s useful. That’s not something we’ve had to do with traditional technology.

AI as a Talking Tool: Why This Changes Everything

The definition of AI literacy also says we need to learn how to use AI as a tool. That seems obvious—of course, AI is a tool. But it’s not just any tool. It’s a tool that “talks.”

It doesn’t just process commands—it responds. It uses human language to communicate with us. And that changes everything.

Think about it—do you own any tools that can talk back? I don’t. I have a toolbox at home, but last I checked, none of my screwdrivers were giving me advice…yet.

That means AI literacy is not just about knowing things—it’s about developing a set of competencies. And those competencies require us to think critically about AI’s capabilities, its limitations, and how we interact with it.

Five Essential Questions for AI Literacy

Long and Magerko, the researchers who developed that definition of AI Literacy, have broken AI literacy into five key questions:

What is AI?

What can AI do?

How does it work?

What should AI do?

How do people perceive it?

The first three questions focus on background knowledge—stuff we can read and memorize. But the last two are particularly important. They are much more abstract and subjective. Those are philosophical questions.

For example, what should AI do? Hmm, let me think about it. Should it help me with my work? If so, which kinds of work — and why? Should I have it give me a recipe for dinner? Why or why not? Should I talk to AI about my feelings? Is that “okay”?

And what about that final question – how do people perceive AI? Is it a fancy tool — or something more? Is it a “friend” - or a screwdriver that can talk? Is it “smart” – or just a very sophisticated parrot?

These are fascinating and important philosophical questions that we have never had to answer before when a new technology comes into our lives. Grappling with them is a crucial part of building Critical AI Literacy. There is no one correct answer, but the more we ask ourselves these difficult questions, the deeper our personal understanding of the tool becomes.

Andrew Ng and the Limits of AI

Now, I’ve been studying chatbots and large language models for the past two years, but there are people who have been studying them for much longer than that. One of them is Andrew Ng, a professor and researcher at Stanford University. One of his insights about AI is particularly useful in helping us understand its limitations.

Ng has pointed out that AI is great at recognizing patterns and making predictions, but it doesn’t actually reason or think the way humans do. It’s really good at handling clear, structured tasks, but the moment you throw it something open-ended, creative, or vague? It starts to struggle.

This distinction is crucial. AI is powerful when given well-structured tasks, but it doesn’t think for itself. If I can clearly define what I need, AI can probably help me. If I can’t, it probably won’t.

This leads to one of the most important principles of using AI effectively: vision and communication are key. If I have a clear vision of my task, I can direct AI in a way that gets meaningful results. If I don’t, I’ll need to adjust how I communicate—or risk AI leading me astray.

At its core, working well with AI is less about the tool itself and more about how I approach it.

Maha Bali: The Role of Reflection in AI Use

According to Maha Bali, a professor at The American University of Cairo, AI literacy isn’t just about knowing what AI can do—it’s also about recognizing what we gain or lose when we use it.

This is where self-reflection comes into play. Every time we use AI, we should be asking:

What am I using AI for?

Why am I using AI?

How am I using AI?

Could I be using it differently?

Through these self-reflective questions, we begin to gain a better understanding of what we gain or lose when we use it. This is not a question that AI can answer; it is a question that only we can answer for ourselves.

Emily Bender: AI as a Stochastic Parrot

Another expert in this space, Emily Bender, a professor at the University of Washington, makes an important distinction about how AI actually works.

She describes chatbots as "stochastic parrots"—meaning they are just predicting the next most likely word in a sequence based on statistical probabilities.

AI isn’t reasoning. It’s not self-aware. It’s just generating text based on patterns in its training data.

This is a critical realization for AI literacy. AI might produce something that looks intelligent, but it doesn’t understand what it’s saying. Because it lacks the true understanding of a wise and self-aware human, AI often runs into a ceiling where we can see its gaps.

This is an important element of becoming a knowledgeable AI user, but there is an additional layer of nuance here. I would urge a recognition that this fact does not necessarily negate its utility. The text that it produces, or the images, or videos – can still be very useful, but it’s important to keep in the back of your mind that AI does not understand the way we understand. Therein, you will be able to manage your own expectations when engaging with a system and subsequently recognize when it has bumped against a certain ceiling.

Bringing Something to the Table

So how else is AI different from us? Well, it’s “memory” of your interactions is not the same as human memory. It can recall key aspects of previous chats, but it does not know you the way another human being knows you from memory. There is no feeling or connection there, and it does not have experience, wisdom, or human judgment. It is not self-aware.

Some people see this as a limitation of AI, but I actually see it as a strength of human intelligence.

Because AI lacks real understanding, it means that we bring something valuable to the table.

We bring:

Experience

Judgment

Context

Reflection

That means AI can assist us, but it can’t replace human decision-making. It also means that together – we might be able to produce something amazing. By combining AI’s ability to string together sophisticated language and my ability to make good choices, we can in some cases act as a potent team.

AI Literacy = Independence

This is why AI literacy is so important. It’s not just about understanding the technology — it’s about maintaining independence in a world where AI is becoming more integrated into everything we do.

Learning AI is like learning a new language. If you travel to a country where you don’t speak the language, you feel helpless and dependent on others. But if you’re fluent, you have freedom — you can navigate on your own.

AI literacy works the same way. The more we understand AI, the better we use it—without becoming overly dependent on it. Research has shown that students with lower AI literacy tend to view AI as “magical” and rely on it uncritically, often using it to complete assignments without fully engaging in the learning process. Those with higher AI literacy, however, see AI for what it is—a tool, not a substitute for thinking. They make better decisions, maintain agency, and critically evaluate AI’s outputs rather than blindly accepting them.

In other words, AI literacy isn’t just about using AI — it’s about using it wisely, ensuring that we control the technology rather than letting it control us.

Why AI Literacy? Why Now?

So, we’ve talked about what Critical AI Literacy is. Now, let’s turn to the why — why this matters right now.

You might be wondering: Can’t we wait? Shouldn’t we hold off until we better understand AI’s benefits and risks? Until we have more definitive data?

Unfortunately, no.

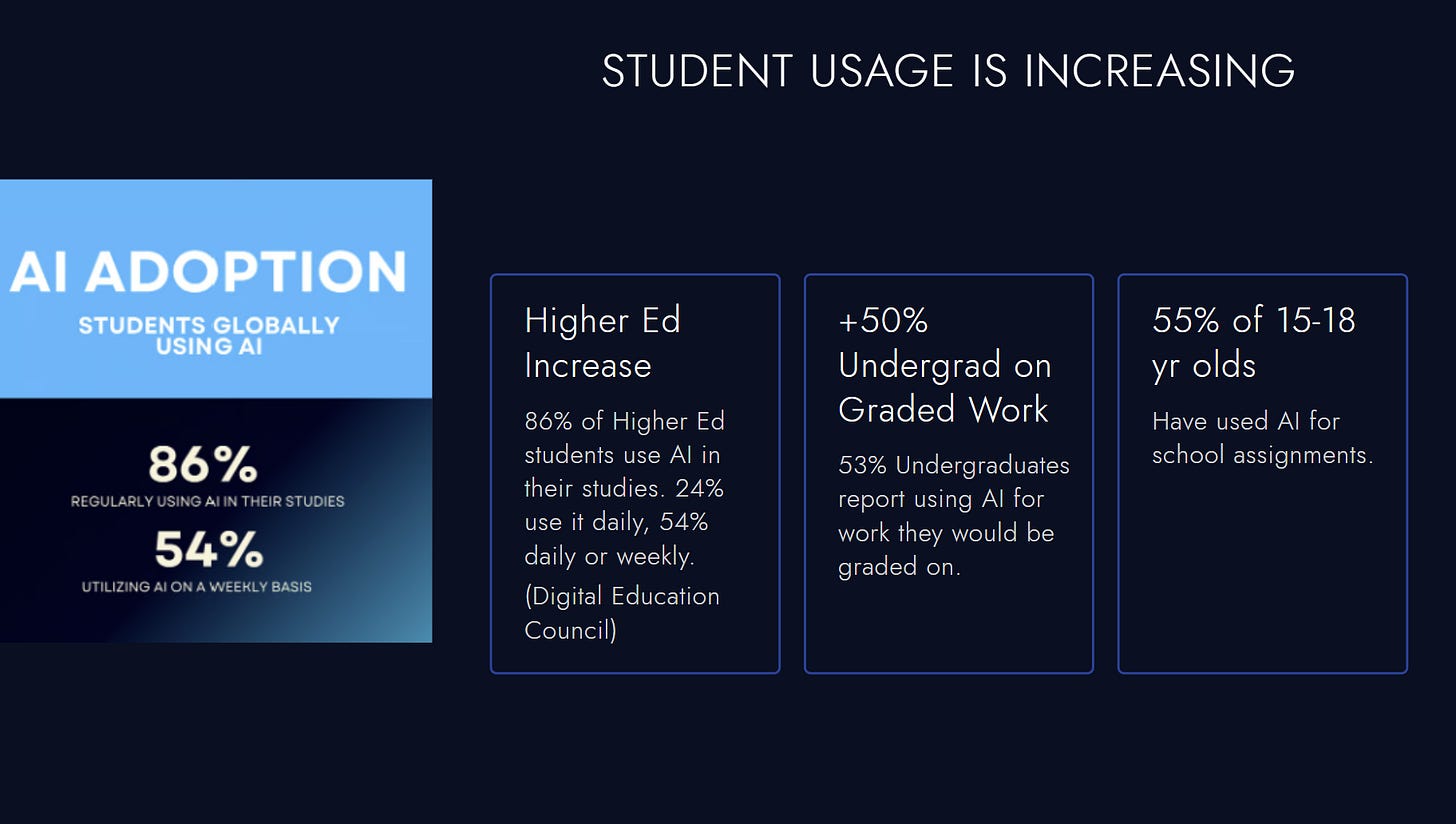

Students are already using AI, and their usage is increasing dramatically. Take a look at these findings from The Digital Education Council and Common Sense Media:

At the same time, employers are prioritizing “AI skills” in hiring. Companies are looking for employees who can help them become more AI-fluent and adaptive. The latest 2024 Microsoft-LinkedIn Work Trend Index Annual Report highlights this shift:

So, the urgency is real. We have to teach students AI literacy now — for three key reasons:

They’re already using it, and without guidance, it could weaken their ability to think critically. AI makes it easy to bypass certain cognitive processes. Without the right framework, students may rely on it in ways that erode their analytical thinking.

AI fluency will be an essential skill in their future. The world they enter will demand the ability to navigate, evaluate, and collaborate with AI effectively. Early research suggests that critically AI-literate thinkers approach these interactions in smarter, more strategic ways.

AI, when used thoughtfully, might actually expand thinking and creativity. This is still emerging, but early indicators suggest that AI literacy isn’t just about avoiding harm—it may also enhance self-awareness and creative potential.

So, the imperative is clear. But that raises a bigger question:

How do we actually teach AI literacy? How do we ensure students use AI well?

It starts with us. We can’t teach what we don’t understand. Before we can guide students, we have to build our own critical AI literacy—and that’s what the next two workshops are all about.

I look forward to working with you on this subject in smaller, more interactive groups.

The Journalism Story: Seeing the Real Story

Before I close out this talk, I want to share a personal story. It’s from 2010, when I was fresh out of college and had just started as a cub reporter for a financial newsletter called Derivatives Week.

It was a small publication covering the over-the-counter derivatives market. For context—I had no financial background and no direct journalism experience. In the first six months of that job, I was drinking out of a firehose. The learning curve was so steep I was absorbing 10 to 20 new things a day just trying to keep my head above water.

One day, I was on deadline. We were required to publish one story per day—daily market updates, industry rumors, legal commentary on regulations, whatever. It was 4 p.m., the deadline was closing in, and I still didn’t have a finished draft.

For the past two hours, I had been stuck in a brutal cycle. I’d type up four or five paragraphs, re-read them, decide they were terrible, highlight the whole thing, hit delete, and start over. I must have done this at least five, maybe ten times.

By the eighth or ninth try, I was furious. I wasn’t just pressing delete — I was slamming it. My frustration must have been obvious because a colleague across the newsroom called out, “What’s the matter, Kentz?”

Without looking up, I pointed at my screen. "There’s no story. The story isn’t there."

She paused. I kept staring at the screen, stewing. Then I looked over at her and saw that look — the all-knowing, slightly amused, you’re missing something look.

“There is a story,” she said. “It’s just not the one you wanted it to be.”

Suddenly, my field of vision narrowed. The frustration in my head went silent — like in movies where the background noise drops out completely.

I looked at my screen again. And she was right. The story was there. It had been in front of me the whole time—I just hadn’t wanted to see it.

I started typing and finished the story in ten minutes.

Why is this relevant to AI and Critical AI Literacy?

Because right now, there are two or three dominant "stories" about AI—stories that are technically true, but not Capital-T True. They’re factually correct in some ways, but they lack nuance. They aren’t wrong, per se—but they aren’t right, either.

And every time I see them, I feel the same sensation I had at my desk in 2010, staring at my screen, convinced there was no story—until I realized I had been looking at it all wrong.

Let me show you what I mean.

The “Pro-AI” Story

This is the story that tells us AI will save time, do all our boring work, make life easier, and teach us everything we want to learn in an instant.

When I see this, I hear that same voice in my head: That’s not the story.

Yes, AI will save us time and automate tedious tasks. But the bar for what qualifies as "good work" is always shifting. What seems groundbreaking today will be routine tomorrow.

In 1999, skillfully searching the Internet for information was a highly valued skill. Now, it's just an expectation. AI won’t just take over tedious work—it will redefine what work is.

And sure, AI can teach me things. It can explain concepts, summarize ideas, and break down information. But it can’t make me an expert.

Expertise requires application, failure, feedback, and iteration. AI can assist in that process, but it can’t replace it. It’s not a magic tutor.

So yes, there’s some truth in this story. It’s not inaccurate.

But still — it’s just not the story.

The “Anti-AI” Story

Then there’s the Anti-AI story—the one that says AI will turn us into human drones, destroy creativity, replace all jobs, and make us intellectually weaker.

Again, I have the same reaction. That’s not the story.

Yes, AI will replace certain jobs. But it will also create new ones that we can’t yet imagine.

Yes, AI can negatively impact critical thinking and creativity. In some cases, it probably will.

But I’ve also seen AI expand thinking. I’ve watched students engage with AI in ways that pushed their ideas further. I’ve felt it in my own creative work—moments where AI has sparked something new, not shut it down.

It’s out there. It’s just not easy to grasp yet.

And that’s the nuance that’s missing. There’s truth in this story, but taken as a whole—it’s still not the story.

So what is the story, then?

Well, here’s the first piece of good news: the story is still being written. That means we have the opportunity to guide it—to carve a path between the extremes of pro- and anti-AI sentiment.

The second piece of good news is that this story is less about AI itself and more about us—if we choose to make it that way. But that requires all of us to get involved. Each of us brings different expertise, skills, and perspectives to this process. The more voices we include, the more nuanced and complete this narrative will become.

Put simply, we need to focus on building Critical AI Literacy—both individually and as a community. By doing so, we ensure that the AI story isn’t just about the technology, but about how we shape it, how we use it, and what we make of it.

Because Critical AI Literacy is the key that unlocks the good and shields us from the bad. AI won’t protect us from ourselves. It’s up to us to engage, experiment, share, and analyze—to thread that needle with intention and care.

At the end of the day, whether we’re talking about AI, Critical AI Literacy, or AI in education, this isn’t just a technology story. It’s a human story. And if we come together thoughtfully, we can ensure that this story leads to progress—not just in what AI can do, but in how we think, learn, and create alongside it.

I look forward to exploring this with you in our upcoming workshops. And for those still on the fence, I encourage you to engage—not to search for definitive answers, but to ask better questions. Because from better questions come deeper, more meaningful understandings.

Thank you for your time and thank you for having me here today.

Brilliant. I wish I had been there to hear it live. I appreciate your insights and the structured way you've presented them, particularly the concluding section on prevailing narratives about AI and your optimistic perspective on co-creating our future with these new tools. It's an evolution of ourselves.

This transformative potential of AI has been anticipated for decades. In the 1980s, for instance, Symbolics, an AI spinoff from MIT's AI Lab, developed the Lisp Machine. Those of us who used the Lisp Machine began to realize the power of what would eventually be in everyone's hands. Now that we have these tools, it's up to us to find ways to make them useful in our own evolution.

Thank you for laying this out in a way that is of value to all.

This is a great conversation! I don't think there is enough discussion around AI as a literacy at this point. Our staff is still more heavily focused on the inappropriate use side and not on the learning side. We have been thinking about AI literacy for a while, working with our AI planning team. We have captured an initial set of ten literacies, along with the creation of a rationale statement. Curious what people think is missing, redundant or lacking clarity?

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1puJw7zghgPhstgwk2_n4H6FmDIidOswGd6rUAdVXaMY/edit?usp=sharing