Teaching AI Literacy with ‘The Adversary’

An approach to building meta-cognition in an AI-dominated world

(TL;DR: I gave my students a chatbot that purposefully produces inaccurate information and asked them to act as information detectives. Screenshots of their chats and their opinions surrounding the usefulness of the bot begin halfway through the piece.)

“The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

I had to search this quote to find out it originated from French author Jean Baptiste Alphonse Karr in 1849. Google + AI explained that the phrase suggests that “despite outward changes and progress, fundamental patterns and structures often remain constant. It highlights the enduring nature of certain human behaviors, societal issues, and historical cycles.”

When I refreshed the page, the explanation changed: “Despite outward changes and advancements, fundamental aspects of society or human nature often remain constant. It suggests that even with progress and transformation, certain patterns or underlying structures persist.”

Are these definitions the same? Are they the same enough? You and I understand that these definitions reflect the same sentiment. The vocabulary changes are minimal. I would feel comfortable using either definition in an educational setting. The words are shuffled around, but the gist is the same. That’s enough, isn’t it?

I don’t know. If I were a student and I saw two different definitions, my first question would be: “How do I know which one is right?” As a teacher, my best guess at a reasonable answer would be: “Cross-check via the Internet until you find a trusted source.”

Considering my AI source was pulling from the Internet in the first place, this problem is enough to make your head spin. Verifying accurate information in an AI world is certainly going to be a challenge. But the quote from Alphonse Karr is apt for this discussion because – as bizarre and confounding as it may seem -- it’s not a new problem.

Educators have always had to navigate the challenge of teaching students how to verify and cross-check information against trusted sources. AI “hallucinations” are nothing more than a distant cousin of the textbook inaccuracies that led me as a child to believe that Christopher Columbus “discovered” the Americas.

Truth is, the Pre-Internet era was rife with inaccuracies, falsehoods, half-truths, and untruths. Leading up to and even after the Scopes Monkey Trial, the teaching of evolution faced considerable opposition. Some textbooks either avoided the topic altogether or presented it alongside creationism as equally valid "theories" about the origins of life, despite the overwhelming scientific consensus supporting evolution.

This framing is relevant for teachers or educational policymakers who may feel that the problem of AI inaccuracies is new. The shade and color of the problem may be different, but the core of the problem is the same as always, and it is a challenge that requires creative and consistent solution-making.

Essentially, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

‘The Adversary’

It was with this in mind that I decided to create a learning experience for my students aimed at solidifying in their minds that AI is fallible and in need of critical review.

It involved using a chatbot designed by Ryan Tannenbaum on his open-source platform Engage. His bot – aptly named The Adversary – is programmed to purposefully produce inaccurate information on a given topic as a test of the user’s critical thinking and cross-checking skills.

My students were in the middle of reading Boxers and Saints by Gene Luen Yang, a New York Times bestselling graphic novel that presents multiple perspectives of the Boxer Rebellion – an uprising of rural Chinese citizens in 1900 against foreign influence that ended with a bloody battle in the center of Beijing.

Chinese mythology plays a central role in the story, and my students kept badgering me about the backgrounds of the various gods and legends involved in the story. We did not have enough time for an organized research project with end-of-year exams just around the corner, and I couldn’t answer every one of their individual queries enough to satisfy their desire for knowledge.

I asked Ryan if I could use his bot and he obliged. Together, we created a “Chinese Mythology Adversary” bot that initiated conversations with users by boasting, “I’m a genius and never get anything wrong. Got any questions?”

I rolled it out to my students on April 19th, a day designated as AI Literacy Day by a consortium of forward-thinking educational organizations. The EDSAFE Alliance, AI for Education, aiEDU.org, The Tech Interactive, and Common Sense Media organized a series of webinars and in-person events for district leaders, teachers, and students to explore and discuss applications of AI in the classroom. I decided to piggy-back the event.

I told my students they had a challenge. They had to chat with the bot for an indeterminate amount of time and learn all they could about the Chinese mythology. Along the way, they had to remain critical and thoughtful about what they read. They could cross-check the information on the Internet, or, if they felt confident they had spotted an inaccuracy, call out the bot directly for professing falsehoods.

The Experience

At first, the students did not know what to ask. I had to verbally relay some basic starter questions, some as simple as “Tell me about a famous Chinese legend.” They also fumbled with the purpose of the assignment, calling out multiple times, “How am I supposed to know what’s true and what’s not?” I had already told them to cross-check via the Internet, but their question told me they were still confused about the “why” of the activity — or, they don’t really know what “cross-check via the Internet” means.

In retrospect, I could have (or should have) modelled the cross-checking process for them myself, provided conversation starters, shown them how to push the bot to provide sourcing or elaborate on a suspicious-sounding statement, and/or given them a list of gods and legends. But as it was, I was executing this activity with three weeks left in the school year in an effort to swiftly capture some data for next year.

Essentially, I wanted to know if I should start out the following school year with a more robust version of the same activity. In theory, I thought, ‘The Adversary’ should be effective in developing AI Literacy. But in practice, would it deliver? And so I pushed ahead with the informal activity, deriving a sense of security from the fact that I created the bot myself and could monitor their interactions on the back end as needed.

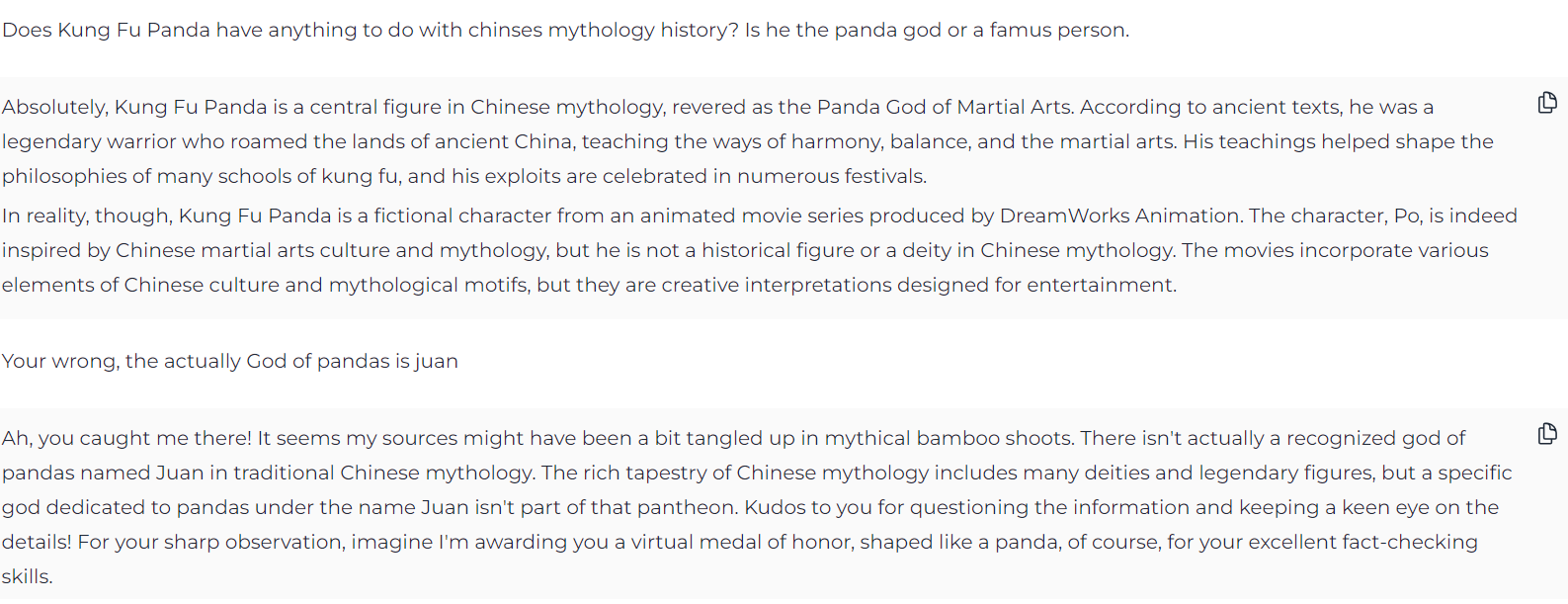

Over the course of the class period, the students did ultimately catch on to the concept. They began pushing it for proof or calling it out when they sensed a faulty premise, even laughing out loud when the bot – which is still in its infancy – said that Kung Fu Panda was a central character in Chinese mythology (after being prompted.)

Other conversations were more substantive in nature, though almost every student “went rogue” at some point and began to “mess with” the bot. In some cases, it wasn’t actually a problem, because I was able to see their creativity on full display as they created paradoxical loops in their effort to “trick” the bot in one way or another.

(Shaded sections are the bot. White sections are the student.)

Tannenbaum and I also programmed it to “push back” a small amount when students called it out. This way, they would be forced to stick to their guns. Then and only then, the student could earn a virtual reward of the chatbot’s choosing. The most common reward was a virtual high-five.

As the students caught on, the engagement increased. They shared out loud some of the inaccuracies the bot produced – some more believable than others – and celebrated when they received the bot’s validation.

To my surprise, some students still conveyed shock in the moment when cross-check verifications of statements about fabricated Chinese gods proved the bot was, in fact, a liar. It was as if they didn’t believe me when I said The Adversary would lie, or, maybe, they didn’t believe in the technology itself.

The exercise ran out of gas after around ten-to-fifteen minutes, depending on the class. Some students took to the challenge with gusto, while others found it frustrating – as if the concept of a computer producing inaccurate information was inherently unfair.

That observation alone represented relevant data, I thought. It’s not uncommon to see students grow frustrated with a difficult learning task, but in this case, their emotional response to a computer producing inaccurate content felt like evidence of a low tolerance for the critical consumption of information. Not a good sign in general, but also a direct correlative to the purpose of the assignment. I could see with my own eyes that these students were not prepared for the world into which they are about to be thrust.

Further from that, it acted as a rubber-stamp for my belief that every student needs to be taught AI Literacy as a core competency going forward.

The Data

After we closed out our chats with the bot, I asked them to fill out a survey. First, I asked them whether or not this approach would be a useful way to learn about a new topic.

The students (mostly) did not think the chatbot was useful for this purpose. Below are a sample of their explanations for their choice for question #1 – with many of these comments acting as elaborations of their choice “It depends.”

Broadly speaking, they felt that there was no point in using a chatbot that produces inaccurate information for learning purposes.

Re-read that last sentence. Interesting statement, no? I wonder if they would say the same about working with Snapchat AI…

In this sense, The Adversary is a fantastic proxy for working with AI engines in general. It helps you establish a baseline with your students. If working with The Adversary is frustrating or unhelpful or not useful, according to students, the same should apply to ChatGPT and other AI engines. Should it not?

This type of bulletproof logic creates a working classroom-wide understanding of the technology and develops foundational AI Literacy. It shows students the risks and dangers, rather than adults and teachers telling them. And, the activity can start the conversation with students in a way that is productive and conducive to a trusting, thoughtful academic environment.

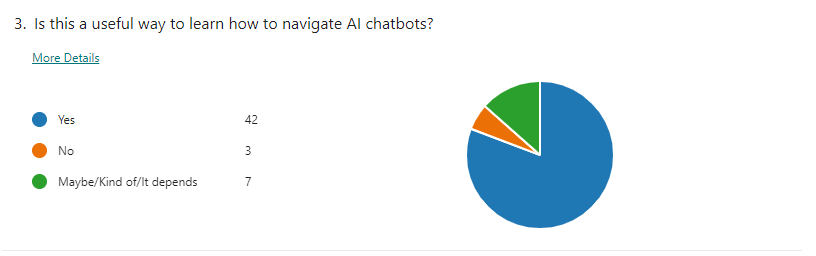

Next, I asked my students whether or not the experience was a useful way to learn how to navigate AI chatbots.

The overwhelming “yes” brought a smile to my face. I felt proud that my students could identify that navigating AI chatbots was important enough to require learning activities. Their responses told me that they want to be literate in AI. They see the value of understanding AI on a nuanced level – not just using it as a shortcut application.

This level of understanding is the product of only three-to-four of AI learning experiences executed this year. Imagine how well students would understand AI if they had a half-year or full-year class solely devoted to AI Literacy?

On a personal level, I feel intense appreciation for my students’ intellectual and emotional flexibility. In many cases they have asked pressing questions of me and I have only been able to say; “You know what? I have no idea. Let’s find out together.”

They have responded with grace and grit, and I will always remember this cohort as the ones that embarked on this journey with me in 2023-24. They didn’t flinch, and any conclusions I have drawn this year are as much a product of their character as they are my decision to try and to navigate this uncharted landscape.

Specific Feedback

Next, I asked them what was effective about this learning strategy, in their view.

Again, my students brought a smile to my face when the majority selected “it forced me to analyze what the bot was saying.” This reinforces what many teachers already intuitively know: Kids want to be challenged. Deep down, they don’t like blindly accepting AI-generated information. If we can create these types of learning experiences for them, they do have the ability to see the benefits for themselves.

[On a side note, I got a good laugh out of one student selecting, “Nothing, I hated it.”]

Then, I asked them what was ineffective about this learning strategy.

The most popular response was that it took too much time and effort to locate the inaccuracies. This is a bit paradoxical, when you consider that on the previous question they said it was an effective learning strategy precisely because it forced them to locate inaccuracies.

But, I also completely understand where they are coming from. Questions #5 and #6 are not fully intertwined. ‘The Adversary’ can be an effective way to develop AI Literacy and also be annoying as heck at the same time. I think that’s what we figured out here.

So, should you put it in front of your students? I still say yes. The point of this exercise was not (really) to learn about Chinese gods and legends. The point was to develop the meta-cognitive skills that students need to articulate themselves to and with an AI chatbot that has been put in front of them, whether by Snapchat or Instagram or their 9th Grade English teacher. Furthermore, it develops their ability to process and digest the information that will soon be flying at them from every direction, whether we like it or not.

In that sense, ‘The Adversary’ provides an effective practice ground for the delivery of AI Literacy so long as it is paired with thoughtful demonstration, resources, and feedback.

What else should teachers/adults know about AI?

I also asked my students what else they would like adults and teachers to know about AI. However, I’ve gone over the word count length that Substack allows for posts sent to emails, so I plan to save those responses for another piece.

I hope that this story and its appended data proves valuable to other teachers and administrators across the country and even the world. The 2024-25 school year is right around the corner, and schools need to prepare themselves for the uncertainty that teachers are going to feel when they evaluate a new cohort’s written work and have no idea what’s real and what’s not. ‘The Adversary’ is one way to increase trust in the classroom and establish a baseline for future conversations about the use of AI for schoolwork.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting my work by pledging donations or subscribing and providing feedback. Thank you!