Use vs. Relationship: What We're Not Asking About AI

How the language we use shapes the technology we build

Claude.ai was used for assistance in researching and drafting this post.

In 1921, Western Electric’s Hawthorne plant near Chicago assembled telephone equipment on a scale that defied imagination. Thousands of workers, mostly women, built the infrastructure of America’s communication network piece by piece. But that same year, executives at AT&T faced a decision that would ripple through communities across the country.

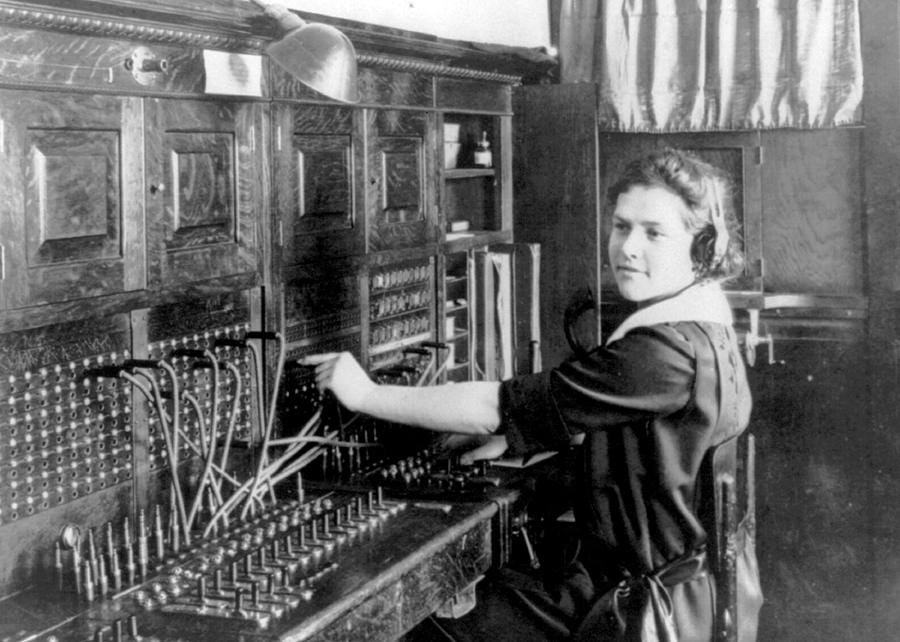

Automatic telephone switching had existed for two decades. The technology worked. It was ready. Small independent phone companies in rural areas had already adopted it. But Bell System executives hesitated. They knew their operators did more than connect calls—they acted as personal assistants, remembered customers’ names, tracked down doctors during emergencies, served as the human voice of the telephone company. In fiction and film, telephone operators appeared as heroic and sometimes subversive figures who saved lives, connected lovers, and held communities together.

So AT&T asked the natural question: What do customers use operators for?

The answer was obvious. Customers used operators to connect calls. That was the function. That was the measurable task. And machines could perform that function faster, more reliably, and without requiring wages, breaks, or collective bargaining.

The decision followed logically. Between 1921 and 1940, AT&T gradually installed automated exchanges across America. Each city converted “one at a time,” as contemporary observers noted. By 1930, only one-third of Bell exchanges had automatic switchboards. By the end of the decade, the transformation was nearly complete.

What’s remarkable isn’t that automation happened—it’s what people discovered they preferred.

Many customers welcomed the change. Automatic systems were developed in part to ensure privacy. Business users no longer had to wait for busy switchboards during peak hours. People who found small talk exhausting no longer had to perform pleasantries to place a call. The machine offered something the human operator couldn’t: predictable, anonymous efficiency.

This preference surprised even the executives who had championed automation. They had marketed dial telephones as modern and convenient, but customers revealed something deeper. They didn’t just tolerate the absence of human contact—they actively chose it. The machine never judged your account status, never gossiped about your calls, never required you to be polite when you were in a hurry.

Yet something else disappeared alongside the operators. In small towns, operators had served as informal emergency dispatchers. When someone called about a fire, the operator didn’t just connect to the fire department—she rang every household on the affected street. During medical emergencies, operators tracked down doctors at dinner parties or movie theaters. They knew which families had cars and could drive people to hospitals. They remembered that the Miller family was out of town and their pipes might freeze.

This infrastructure wasn’t recorded in any job description. It emerged from relationships operators had with their communities. When automation arrived, there was no line item for “emergency network coordinator” or “community information hub” because those functions had never been formalized. They simply evaporated.

One historian later described telephone operators as “the fingertips of the country” - the human touch points in a vast technical system. When the system became fully automated, those fingertips were amputated. Cleanly. Efficiently. Irreversibly.

The language AT&T used made this outcome seem inevitable. “Function.” “Efficiency.” “Cost reduction.” These words framed operators as performing tasks that could be measured, optimized, and potentially automated. The vocabulary of use - what customers used operators for - created a narrow field of vision that excluded everything operators provided that wasn’t strictly transactional.

But imagine if the question had been different. Not “What do customers use operators for?” but “What is the customer’s relationship to the operator?”

That question would have revealed complexity. Some customers wanted connection and community. Others wanted privacy and efficiency. Some valued the human judgment operators provided during crises. Others resented the social performance required to make a simple phone call. The relationship customers had with operators wasn’t uniform - it varied by personality, location, and context.

If AT&T had asked the relationship question, they might have designed differently. Hybrid systems that preserved human operators for emergencies while automating routine calls. Opt-in services for customers who valued human connection. Community backup networks to replace the informal infrastructure operators had provided.

Or maybe not. Maybe the economic pressure toward full automation was too strong. Maybe customers’ preference for impersonal convenience would have won regardless.

But at least there would have been a conscious choice. At least people would have seen what they were trading. At least the decision would have been visible rather than hidden inside the language of efficiency.

We’re having similar conversations now about artificial intelligence. Businesses ask: “How can we use AI to improve productivity?” Educators ask: “How are students using AI to complete assignments?” Policymakers ask: “What are the use cases for AI in healthcare, transportation, finance?”

The language is identical to what AT&T used in 1921. Usage. Function. Efficiency. Task completion.

And just like in 1921, this language shapes what we can see. When we ask about AI usage, we can measure time saved, costs reduced, outputs generated. We can compare AI performance to human performance on specific tasks. We can optimize for efficiency.

What we can’t see is the relationship dimension. The ways people are forming dependencies on AI that they can’t articulate. The judgment skills that atrophy when we outsource decisions to algorithms. The human connections that dissolve when machines handle interactions previously managed by people. The informal knowledge systems - like those telephone operators maintained - that disappear without leaving traces in our efficiency metrics.

This doesn’t mean AI is bad or that automation is wrong. The telephone operator story isn’t a morality tale about evil corporations destroying community bonds. Many operators hated their jobs - the stress was documented, the wages were low, the monitoring was oppressive. Many customers genuinely preferred machines. Efficiency gains were real and substantial.

But the story does suggest that the language we choose determines what we can think about.

“Use” language makes certain trade-offs invisible. It focuses our attention on measurable outputs while obscuring relational dimensions. It treats technology as a tool applied to tasks rather than as something we live with, depend on, and are shaped by.

“Relationship” language would ask different questions. Not just “How should we use AI?” but “What kind of dependency are we building?” Not just “Is AI helping or hurting learning?” but “How does AI change students’ relationship to struggle, to knowledge, to their own thinking?”

I don’t know if changing our language would change our outcomes. Language is slippery. People resist new vocabularies, especially ones that make simple decisions feel complicated.

But I know this: In 1921, AT&T didn’t have the language to examine what customers were trading for convenience. The social infrastructure of telephone operators disappeared before anyone realized it was infrastructure at all. By the time people could see what was lost, it was already gone.

With AI, we’re at a similar inflection point. We’re making decisions about what to automate, what to optimize, what to replace. We’re using the language of use and efficiency to guide those decisions.

Maybe we should try different words before we reach the point where we need them.

Thanks for reading. If you’re interested in more posts like this, hit the subscribe button below - or pass along to a friend who might find it interesting.

Powerful reminder. Framing AI in terms of “use” risks obscuring the relational and societal impacts, just as AT&T overlooked the invisible infrastructure operators provided.

I cover the latest AI insights and how our relationship with technology shapes its impact. If you’re interested in understanding the deeper effects of AI beyond efficiency. Check out my Substack, you’ll find it very relevant.

Love this!