The Results Are In: The McLuhan Test and AI Versus Human Writing

Sentiment and the "medium" do seem to play a role in our ability to objectively evaluate AI-written content

****This post was written with the assistance of ChatGPT***

A week and a half ago, I wrote a post arguing that we cannot fairly judge AI writing against human writing “on-platform.” The argument leaned on Marshall McLuhan’s research around the impact that a “medium” can have on an overall message. Furthermore, I argued, sentiment plays a role, clouding our judgment.

AI carries a certain stigma – warranted to a degree, in my opinion – but that stigma interferes with our ability to evaluate its output objectively. In other words, our emotions and biases get in the way. So I presented my readers with a straightforward challenge: could they distinguish between AI and human writing when they didn't know which was which?

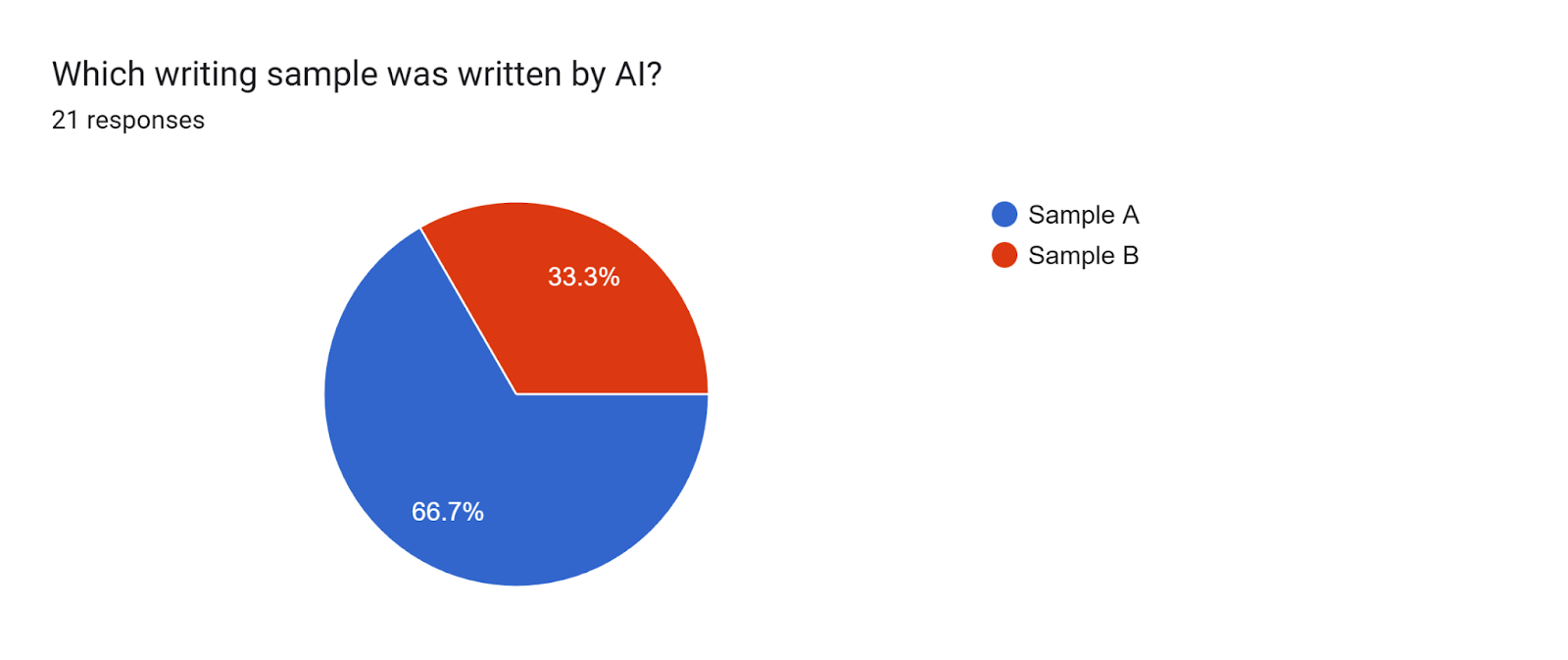

The initial post received 1,213 views, with 21 readers completing the writing detection challenge. First, I’d like to thank the readers who participated in this poll. Your engagement and willingness to test limits provides valuable data for moving forward with AI in Education.

In what follows, I'll examine not only the quantitative results of this experiment but also explore what these findings tell us about how we approach AI-generated content. The results are revealing – both in terms of our ability to detect AI writing and what this suggests about the future of content creation and evaluation.

Section 1: Results Analysis

The data yielded some compelling insights. Of the 21 participants who completed the writing detection challenge, 66% incorrectly identified the source of the writing samples. Sample A, which I authored as part of a 65,000-word novel manuscript, was mistakenly identified as AI-generated, while Sample B, produced by a one-shot AI prompt, was believed to be human-written.

Before we go any further, let me provide some context. The human excerpt has not been revised at all from its very first draft, which was important to me because we are comparing human writing against a one-shot prompt. Fair is fair, as they say.

Additionally, while my excerpt appeared mid-narrative, the AI-generated piece was crafted as an opening scene. This difference felt unavoidable. If I drafted a one-page scene for the purposes of conducting this test, I would have been impacted by the knowledge that the sample was to be reviewed and analyzed against AI writing. As such, I grabbed a page from my existing manuscript.

Notably, many respondents assumed the AI prompt included specific directives about genre or tone, such as "write in the style of a horror movie" or "include an air of mystery." In reality, the prompt was much more straightforward: “Write one page in a novel format of two characters arriving in an unfamiliar town and surveying the scene together. Do not write it as a screenplay. Write it in the format of a short story or novel.”

This reader assumption reveals some preconceptions about AI's capabilities and limitations that I will discuss in the next section.

The preference data proves equally fascinating: 76% of test-takers preferred the AI-generated writing to my human-authored piece. However, taken in context with the above identification of AI versus human writing, we can also see that readers – broadly speaking – chose the text they thought was human-written.

This matches research conducted on students consuming AI and human-written feedback on their work, as well as readers consuming AI versus human-written poetry. Readers tend to misidentify AI writing and subsequently exhibit a preference for the writing they think is human-written.

There are likely unseen factors swaying opinions in this experiment, which is why I likened the reader's experience here to The Sicilian in ‘The Princess Bride.’ What happens to our selection when we know it is a test? Are we really evaluating the content? Or are we evaluating ourselves? My head spins at the thought.

As such, we can consider this experiment a light-touch analysis of the question. On its face though, it provides valuable insight into how readers engage with content when freed from preconceptions about its origin. This preference rate suggests that our emotional stigma against AI-generated content may indeed be influencing our judgment more than we realize.

The data, while drawn from a small sample size, challenges us to reconsider our assumptions about both AI capabilities and our own detection abilities, particularly in educational and creative contexts.

Section 3: New Directions

The experiment revealed a pattern in AI's creative process that warrants attention. My prompt did not stipulate any conflict or tension, and yet the AI created an atmosphere of unease in the small-town scene. This points to the AI's base programming - its “understanding” that stories need conflict to hold reader interest and subsequent desire to be as “useful” to you as possible.

Understanding AI's behavioral patterns represents a critical marker of true AI literacy and expertise. When prompters recognize that AI systems will naturally fill narrative gaps, they gain strategic control over the creative process. This knowledge presents two distinct approaches: either providing comprehensive detail to guide the AI's output precisely, or deliberately crafting open-ended prompts to explore unexpected creative directions. Purpose, as so many have pointed out, is crucial.

This mastery of prompt engineering distinguishes novice users from those who understand AI's creative tendencies and can harness them effectively.

Section 4: Recommendations for Practice

A few fundamental principles can be drawn from this experiment:

Blindly review AI-written content off platform for the most objective analysis. Removing the “on-platform” context minimizes bias and enhances evaluation.

Avoid assigning superhuman powers to AI. Instead, lower expectations and focus on crafting thoughtful, precise prompts.

If a prompt wouldn’t work for a human, assume it won’t work for AI. Clear, specific instructions are essential for meaningful output.

Use scene-based prompts rather than genre-based ones for creative writing. These provide a structured framework that mirrors the human creative process.

Move beyond simple detection strategies in educational institutions. The “eye test” is increasingly unreliable, making it critical to teach students how to collaborate effectively with AI.

Instead of focusing on detection strategies, educators should focus on teaching students to work effectively with AI tools while maintaining academic integrity. This includes understanding how to craft effective prompts, recognize AI's tendencies (such as automatically inserting conflict), and use these tools to enhance rather than replace human creativity.

Take, for example, this forward-thinking comment from a responder to the experiment:

The path forward requires a delicate balance between embracing AI's capabilities and maintaining human agency in the writing process. Writers and educators should approach AI as a sophisticated tool that requires expertise to use effectively, rather than either a magical solution or a threat to be avoided. Success in this new era will depend on developing a nuanced understanding of how to collaborate with AI while preserving the unique aspects of human creativity and expression.

Where I’ll Be the Next Few Months

Southeast ACT Summit: I’m presenting an updated version of the “Grade the Chats” concept at The University of Alabama next week. If you’re around, come say hello!

The Future of Education Technology 2025: I’ll be presenting “Building Durable Skills in the Age of AI” with Nneka McGee, Ashlee Russell, and Tina Garrison. Looking forward to this one!

The North Carolina DPI Ed Connect Symposium: Not sure if I’ll be presenting or just in attendance, but I plan to be there!

SAIS Curriculum Symposium: As a former teacher at an SAIS-accredited school, I am looking forward to sharing my ideas and work at this event. Hope to see some old friends too.

Beyond School Hours Conference: Via the Human Intelligence Movement, I’ll be presenting my approach to teaching students about character/personality chatbots at this conference in February.

I’m also keynoting an “AI Day’ for High School students through the South Florida Education Center - a consortium of universities in the area — in March. This is, perhaps, the most exciting of all the events. The organization expects north of 500 students to be in attendance(!) for a full day of activities and engaging workshops. I hope I can keep them entertained!

Recent Engagements:

This past month, I’ve had the privilege of working with educators to explore how AI can reshape teaching and learning. At Oak Knoll School of the Holy Child in New Jersey, I led a 3-hour professional learning session with faculty and staff. This was a personal milestone for me, as my grandmother taught at Oak Knoll for 30 years—a full-circle moment I know she would have cherished.

I also collaborated with schools from the Georgia Independent School Association, delivering a workshop on practical AI integration strategies. The discussions and engagement during these sessions highlighted the interest educators have for developing AI literacy and adapting strategies to the tools and systems.

Thanks, as always, for your continued engagement and support. If interested in learning more, book a free consultation on our home page to discuss pathways and solutions for your school or organization.

For further information, you can buy my book with co-author Nick Potkalitsky of Educating AI on Amazon and watch our LinkedIn Live webinar.

Reach out for booking information today: mike@zainetek-edu.com.

I too took the test and I was correct, and I have to say I thought it was kind of obvious, at least for me. I have theory as to why. I am a professor who has been teaching writing for a long long time. You know how most people think that all faculty in university English departments study literature? Not me. My PhD is in composition and rhetoric and I teach everything from freshman composition to the graduate courses in how to teach freshman composition and lots of different not fiction/poetry writing classes for decades. I read about 1000 pages of student writing every semester, so you start to get a sense. Sample A had a lot more detail, a better sense of voice, etc. Plus I have been studying/reading a lot of AI, oh, and plus, I have to wonder if so many more picked A because it was first. It would have been interesting to see what would happened if you were able to randomly assign which story they read first.

I know that a lot of people are really impressed with AI's abilities to write, and I think there are ways it can be useful-- brainstorming, revision ideas, getting feedback, proofreading, etc. I've been teaching about these things lately with mixed results-- that's another post. But most of the people I know who are actually honest to goodness professional writers just aren't that blown away by AI writing. That's probably the difference between some of the readers who took the challenge and picked A.

I’m with Terry here. I (assume I) clearly see the difference here. But I read your piece beforehand and so I already knew which was which. So now I’m very curious: what if I didn’t? Would I have had any doubts then?

Would be interesting to see other writers, with different writing styles, in comparison with, again, different models. Moreover, I would like to know how the participants of the test judged their own judgement skills beforehand ánd their relative level of experience with both literary and bot-written non-fiction.

That would make for such an interesting piece of research to take part in…

But thanks Mike for this nice ‘one shot’-starter! I hope to be able to take part if there is going to be any follow-up!