The Medium Blinds Us: How AI Sentiment Shapes Our Judgment

How Medium and Emotion Cloud Our Evaluation of AI-Generated Content

***This post was written with the assistance of ChatGPT.***

I wanted to take a moment to thank you for your continued support AI EduPathways!!! Please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Take advantage of the yearly rate discount. $50 at year = $4.16 per month.

On Wednesday, Leon Furze wrote that AI is coming for writers. His piece represents part of a growing backlash against OpenAI and other tech companies from professionals in the field of creative writing. His thesis rests partially on the idea that AI neither produces quality creative writing (nor writing in general) nor can replace the important processes involved in producing effective written communication.

His conclusions, however, rest on a flawed LinkedIn experiment/poll that deserves analysis.

Leon shared ChatGPT creative writing outputs and asked people if they thought they could be qualified as good writing. Unsurprisingly, the post got a lot of attention. Even more unsurprisingly, a lot of people said they thought it was bad. That’s the popular line these days, and most people are afraid to do anything other than toe it.

Here's an anonymized quote that illustrates this:

"Holy hell in a handbasket. Not enjoyable and also not readable. Apart from that, not a huge amount of story coming through. But aesthetics seem to have been successfully deprioritized as prompted, so that's kind of a win except for anyone reading the thing."

Each person is entitled to their own opinion. Whether the AI writing in the post was good or bad is not my concern. My issue is with the test itself.

The fundamental problem with this experiment is that Leon revealed the AI origin of the text. In fact, he showed it happening in real-time.

Why is this a problem?

Because ‘The Medium is the Message’

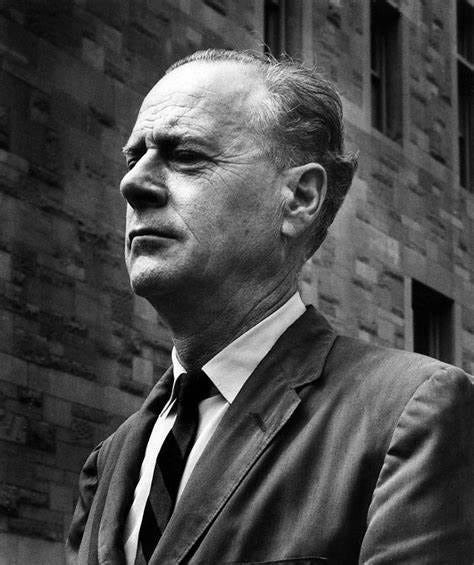

"Indeed, it is only too typical that the 'content' of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium." ~ Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964

Asking readers to evaluate GenAI content directly from the medium of an AI platform itself is an ineffective strategy and a flawed experiment because “the medium is the message,” as Marshall McLuhan famously concluded in his groundbreaking 1964 work Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man.

In his research, McLuhan argues that the form or medium through which a message is delivered has a greater influence on society and the way we perceive information than the actual content of the message itself. McLuhan was not arguing that content is irrelevant, but rather that the way content is communicated reshapes our understanding of the world, often in ways that are more impactful than the content alone.

GenAI platforms such as ChatGPT and Claude represent entirely new mediums with which we as human beings have no established frame of reference. Attempting to analyze AI transcripts “on-platform” often leads to misconceptions, confusion, and cognitive roadblocks due to our inability to grasp the impact that the medium has on our ability to properly process and engage with the content.

(Side Note: This concept is one of the four pillars of The Field Guide to Effective AI Use, a digital exhibit a group of collaborators and I have under review with the WAC (Writing Across the Curriculum) Clearinghouse (tentative publication date: January 2025).

Viewing our AI usage through mediums that are more familiar to us, like printed out paper or a Microsoft Word document, acts as a lever to shine a new light on the quality of AI outputs as well as methods for defining safe and effective use habits (i.e. defining quality inputs and interactions.)

Furthermore, knowledge of the source plays a major role in shaping our perceptions. A research report published in July supports this notion. A group of students were given feedback from a human teacher and an AI teacher and provided a set of survey questions.

From the Abstract:

“Disclosing the identity of the feedback provider affects students’ preferences, leading to a greater preference for human-created feedback and a decreased evaluation of AI-generated feedback.”

This, I argue, is what happened on Leon’s post.

But, wait! There’s more!

“Moreover, students who failed to identify the feedback provider correctly tended to rate AI feedback higher, whereas those who succeeded preferred human feedback. These tendencies are similar across academic levels, genders, and fields of study.”

So, not only does the medium play a role, but identification of the source and surrounding sentiment does too. When students knew it was AI, they didn’t like it. When they didn’t know it was AI, they liked it more.

How is current sentiment affecting your judgment?

This highlights a reality some in AI education - especially in writing — refuse to acknowledge.

Many of us prejudge AI content negatively because we know its source. Or we criticize it because we want it to be bad. Our emotions impede objective analysis - we scrutinize AI output more harshly than if a colleague shared identical text via email.

Furthermore, we believe that if we say that AI content is bad enough times, it will become true, like a collective facade that everyone agrees to respect in the hopes of maintaining a blissful shield. Think of The Wizard of Oz. Especially if you are an educator or a writer, you are likely (and rightly) very mad and cannot see through the red veil of your emotions. I include myself in that camp.

My argument in this piece is not that AI writing is good. Nor is it that AI should necessarily be included in every aspect of a writing curriculum. I do believe that we need to teach students how to use AI safely and effectively, and I do not believe that the current #resistAI trend is a good thing. However, my argument here is that we need to clear our vision and begin reviewing AI use through a crisper lens, one that is less clouded by the pendulum of human emotion.

If you disagree, here's your chance to prove me wrong.

Here is a test. Attached, you can find a Google Document with two samples of text and a Google Form to log your responses. One is generated by a human, the other is generated by AI. Each is separated from their original medium and anonymized. We have removed the variables of the AI medium and the sentiment which surrounds it. Read through them. Then, enter into the Google Form and tell me which writing sample you feel is better, and which you think is AI.

Bonus points to folks who explain A) why they think one is AI and the other is human (what tipped you off?) and B) why they like one over the other (no wrong answers).

I’ll reveal the results after a week. Perhaps I am wrong. Perhaps I am right. The only way we will know is if you engage.

Conclusion

Either way, let’s be honest about how our emotions might be getting in the way. Let’s be honest about how the medium affects the message. Let’s analyze AI with clear eyes so that we can better generate a meaningful future.

Evolve Your School’s AI Landscape

Zainetek Educational Advisors provides consulting, curriculum design, and professional development services to educational institutions and organizations seeking to develop a healthy approach to AI adaptation.

Book a free consultation on our home page to discuss pathways and solutions for your school or organization.

Zainetek’s School Adaptation Framework:

For more information, you can buy my book with co-author

of on Amazon and watch our LinkedIn Live webinar from last week.Reach out for booking information today: mike@zainetek-edu.com

I like your honesty.

I would add the missing reason for all of your aforementioned misidentification - a pervasive materialistic world view. A total, all-coating belief that life is just data, small particles of matter behaving, turning, churning through unmutable and non-changing laws. Organic life is not considered, it's actually an illusion and the properties of organic life we once assumed - are all consigned to inert matter. Man as a machine, in essence.