When Brain Science Meets AI: What Executive Functioning Teaches Us About Learning with Technology

Finding a new way to think about safe and effective AI use

Next week, I'm presenting at Ohio Wesleyan University about AI fluency and educational technology. The faculty will hear a talk on executive functioning right before mine, which got me thinking: What if executive functioning provides a missing lens for understanding safe and effective AI use?

I've spent years teaching students and adults how to craft better prompts, verify AI outputs, and integrate these tools into their workflows. These technical approaches remain valuable, but I'm discovering that there's a deeper cognitive foundation at work. Users who excel with AI aren't just technically proficient - they demonstrate strong executive function skills that make any complex tool more effective.

Here's my problem: I know very little about executive functioning beyond buzzwords. I can't teach what I don't understand, and I can't measure what I can't define. So this blog is my public commitment to learning, and eventually bridging, these two critical domains.

What Executive Functioning Actually Is

A cursory dive into the executive functioning literature has already revealed some fascinating connections that I think are worth exploring, even from my novice perspective.

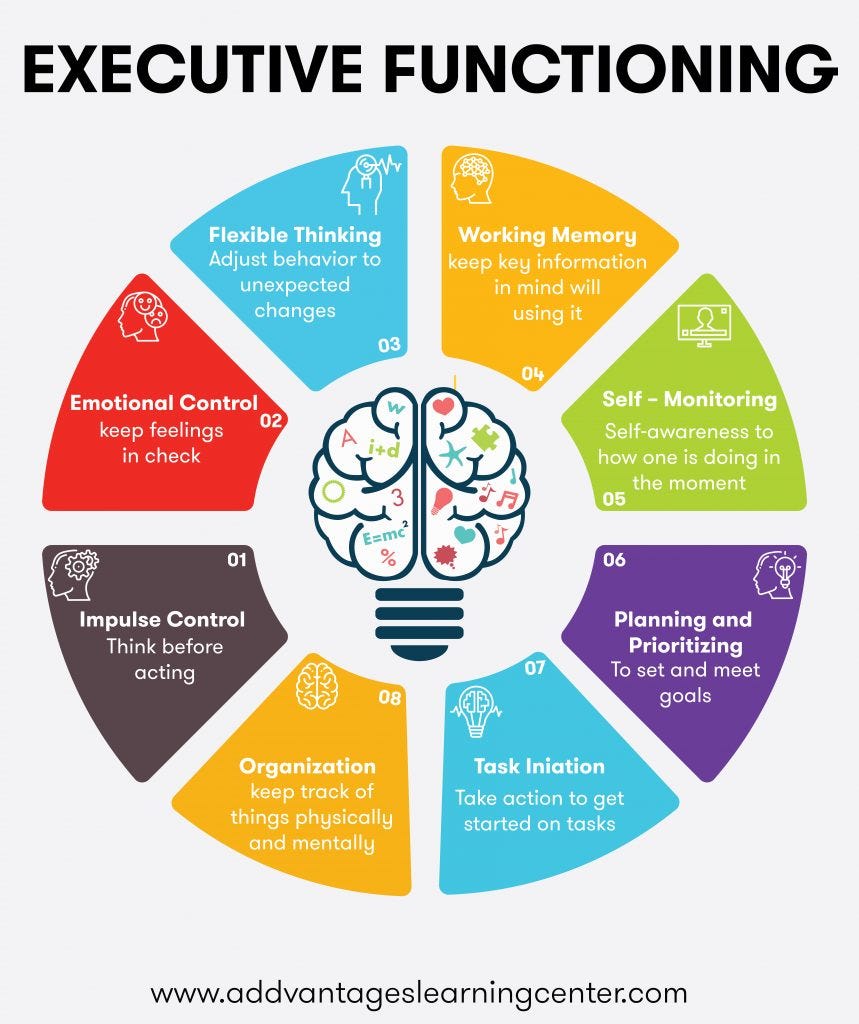

Executive functions are the mental skills that control and regulate other abilities and behaviors. Think of them as the brain's air traffic control system. It’s the process of coordinating, directing, and managing the constant flow of cognitive processes.

The Big Five:

Working Memory - The ability to hold information in mind while using it. It's not just remembering your grocery list; it's keeping that list active while navigating the store, calculating costs, and making substitutions.

Cognitive Flexibility - Mental agility that lets us switch between thinking about different concepts or adapt when rules change. It's the difference between rigidly following a recipe and adjusting when you're missing an ingredient.

Inhibitory/Impulse Control - The capacity to control attention, behavior, thoughts, and emotions to override strong internal predispositions. It's what stops you from blurting out the first thing that comes to mind or clicking "send" on that angry email.

Planning and Organization - The ability to manage current and future-oriented task demands, set goals, develop strategies, and monitor progress.

Self-Monitoring - The awareness of one's own thinking processes and the ability to evaluate and adjust performance in real-time.

A Quick History Lesson

The concept emerged from neuropsychological research in the mid-20th century, particularly through studies of patients with frontal lobe damage. Researchers like Alexander Luria and later Muriel Lezak observed that people with certain brain injuries could perform individual tasks but couldn't organize or regulate their behavior effectively.

The term "executive function" was coined by Lezak in the 1980s, drawing an analogy to business executives who don't necessarily perform every task but coordinate and oversee operations. The field exploded in the 1990s and 2000s as researchers developed better tools to measure these skills and understand their development across the lifespan.

How Schools Teach and Assess These Skills

Teaching Approaches

Direct Instruction Methods:

Explicit strategy instruction (teaching specific organizational systems)

Metacognitive training (teaching students to think about their thinking)

Goal-setting and self-monitoring protocols

Time management and planning frameworks

Embedded Approaches:

Incorporating EF skill development into subject-area instruction

Using games and simulations that require executive control

Scaffolding complex tasks to gradually build independence

Creating classroom environments that support EF development

Intervention Programs:

Tools of the Mind (early childhood)

Cogmed (working memory training)

Brain Age and similar cognitive training programs

Measurement Tools

Behavioral Rating Scales:

Teacher and parent observation protocols

Performance-Based Assessments:

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (cognitive flexibility)

Stroop Test (inhibitory control)

Tower tests (planning)

Digit span and n-back tasks (working memory)

Ecological Assessments:

Real-world task performance

Academic outcome measures

Functional behavior analysis in natural settings

The Measurement Transfer: From EF Assessment to AI Fluency Evaluation

Here's where the parallels become practically powerful: measuring safe and effective AI use is inherently difficult, but so is measuring executive functioning. The good news is that decades of EF assessment development provide a roadmap for evaluating AI fluency skills.

Consider how we might transpose existing EF measurement techniques onto AI interaction assessment:

Behavioral Rating Scales for AI Use: Instead of rating a student's general planning abilities, we could develop observation protocols that assess how they approach AI interactions—Do they set clear goals before engaging? Do they monitor their progress during conversations? Do they reflect on outcomes afterward?

Performance-Based AI Tasks: Just as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test measures cognitive flexibility by requiring rule-switching, we could design AI interaction tasks that require students to pivot strategies when initial approaches fail. Instead of the Stroop Test measuring inhibitory control with color-word conflicts, we might measure students' ability to resist accepting immediately appealing but low-quality AI outputs.

Here’s an example. About 18 months ago, I created an AI bot I originally called "The Adversary" (now renamed "The Hallucinator") that deliberately provides false information to students. Students know upfront that the bot will lie to them, transforming the interaction into a direct test of executive functioning skills.

Here's how it works: Students research a specific topic and are tasked with "catching" the bot's hallucinations. The bot is programmed to stand its ground when challenged, creating cognitive friction that forces students to demonstrate conviction in their knowledge and reasoning. What emerges is a fascinating exercise in dual-level thinking. Students must simultaneously engage with the content (System 1) while monitoring their own cognitive processes and the bot's reliability (System 2).

The exercise reveals executive functioning in action: students with strong working memory maintain their research findings while engaging with contradictory information; those with good inhibitory control resist the bot's confident-but-false assertions; students with effective self-monitoring catch themselves when they start to doubt their own knowledge in the face of AI pushback. You can read more about the exercise here, and you can try out a version of the bot yourself here.

Ecological AI Assessment: Rather than observing executive functioning in classroom settings, we could analyze authentic AI interaction logs, looking for patterns that indicate strong self-regulation, strategic thinking, and metacognitive awareness during real AI use.

This approach aligns perfectly with emerging standards from organizations like the TeachAI consortium and OECD, which emphasize competencies like "manage AI" and "create with AI." These aren't just technical skills—they're executive function applications in AI contexts.

"Manage AI" requires the same planning, monitoring, and self-regulation skills that traditional EF assessments measure, just applied to human-AI collaboration. "Create with AI" demands cognitive flexibility to iterate between human and AI contributions, working memory to maintain creative vision across multiple interactions, and inhibitory control to resist letting AI drive the creative process entirely.

By adapting proven EF measurement techniques, we could develop robust, validated assessments for AI fluency that go beyond surface-level prompt evaluation to measure the deeper cognitive skills that enable safe and effective AI use.

Why This Matters More Now Than Ever

The AI Amplification Problem

Every interaction with AI requires executive function skills, but unlike traditional tools, AI can mask EF weaknesses while simultaneously amplifying them.

Working Memory Demands: Effective AI use requires holding multiple elements in mind simultaneously - the original goal, context from previous exchanges, awareness of the AI's limitations, and evaluation criteria for outputs. Students with weak working memory often lose track of their purpose mid-conversation with an AI tool. This connects directly to what I call "prompt jumping without clear goals,” or the tendency to move from query to query without a coherent purpose.

Many educators have adopted "AI Reflections" at the end of assignments, but we're missing the front end: pre-prompt purpose statements that force students to articulate their goals before engaging. Even more powerful are "Mid-Interaction Interruptions.” These are structured pause points during AI conversations that ask: "Are you still aligned with your original purpose? What have you learned that changes your approach?"

Cognitive Flexibility Requirements: AI tools don't always work as expected. The same prompt that worked yesterday might fail today. Users need the mental agility to recognize when an approach isn't working and pivot to new strategies without getting stuck in ineffective patterns.

Inhibitory Control and the Bullshit Detection Problem: Verification and evaluation of AI outputs is not just about fact-checking - it's about recognizing when AI outputs are sycophantic, overly agreeable, or intellectually hollow. Students need to develop what I call "bullshit detection" skills, which require inhibitory control to resist seductive but substanceless responses.

Unfortunately, there's a catch: effective bullshit detection requires domain expertise. Students can only recognize when an AI response lacks depth, nuance, or accuracy if they already have some knowledge in that area. This suggests we shouldn't encourage AI use in fields where students lack foundational experience - they simply don't have the cognitive resources to evaluate quality.

Planning and Self-Monitoring: The Patience Paradox: BCG Consulting research confirms what I've experienced: breaking problems into subcomponents leads to dramatically better AI outputs. But what most people miss is that effective AI collaboration takes as much time as doing the work without AI, just distributed differently.

Students expect AI to be a shortcut, but the most successful AI users exercise extreme patience and thoroughness. They chop problems into the smallest possible pieces, provide extensive context, and treat each interaction as part of a larger strategic process. The time investment doesn't decrease - it shifts from execution to orchestration, planning, and verification.

Beyond Individual Performance

Academic Integrity Implications: Students with weak executive functions may be more likely to inappropriately rely on AI, not from malicious intent but from poor self-regulation and planning skills.

Workplace Readiness: As AI becomes ubiquitous in professional settings, employees who can effectively collaborate with AI tools—which requires strong EF skills—will have significant advantages.

Democratic Participation: In an era of AI-generated content, citizens need executive function skills to critically evaluate information, resist manipulation, and engage thoughtfully with complex issues.

Lifelong Learning: As AI tools evolve rapidly, the ability to adapt, learn new systems, and transfer strategies across platforms becomes crucial—all executive function dependent skills.

The Metacognitive Revolution

Perhaps most importantly, AI use requires constant metacognition. Essentially, awareness of what you know, what you don't know, and how well your current approach is working. Students need to:

Recognize when they're out of their depth and need verification

Understand their own cognitive biases and how they might influence AI interactions

Monitor their dependence on AI tools and maintain human capabilities

Reflect on the effectiveness of different AI collaboration strategies

Connecting Teaching Methods Across Domains

Here's the breakthrough insight: we can directly apply established executive function teaching methods to AI fluency education. The pedagogical frameworks already exist—we just need to redirect them.

But there's a crucial shift in focus. Traditional EF instruction emphasizes organizing your physical and digital environment—color-coded planners, structured note-taking systems, time-blocking calendars. While these remain valuable, AI-age executive functioning is fundamentally about organizing your thoughts before, during, and after AI interactions.

This is why I believe the most powerful intervention isn't teaching better prompting techniques—it's teaching students to journal about their AI use. Not journaling with AI as a writing partner, but journaling about AI as a metacognitive practice.

Pre-interaction journaling forces students to articulate their goals, assumptions, and success criteria before engaging with AI tools. During-interaction reflection helps them monitor their thinking and catch themselves when they drift from their purpose. Post-interaction analysis builds pattern recognition about what works, what doesn't, and why.

This kind of reflective practice around AI use develops the same cognitive habits that traditional EF instruction targets—self-awareness, strategic thinking, and behavioral regulation—but applied to the specific challenges of human-AI collaboration.

The students who struggle most with AI aren't lacking technical skills; they're missing the metacognitive frameworks that would help them think clearly about their thinking during these interactions. Teaching them to externalize and examine their cognitive processes through structured reflection is how we bridge traditional EF instruction with AI fluency demands.

The Path Forward: A Personal Learning Commitment

Phase 1: Foundation Building

Study the core EF research literature

Interview educators who specialize in EF instruction

Observe EF assessment and intervention in practice

Connect with researchers in both EF and AI fluency domains

Phase 2: Bridge Construction

Develop frameworks that explicitly connect EF skills to AI fluency

Create assessment tools that measure EF skills in AI-use contexts

Design instructional approaches that build both domains simultaneously

Pilot interventions with students and educators

Phase 3: Community Building

Share findings through academic and practitioner channels

Build collaborative networks between EF specialists and AI educators

Advocate for integrated approaches in educational policy and practice

Where This Goes From Here

Executive functioning provides a powerful new lens for understanding and teaching safe AI use. Rather than treating AI fluency as a separate skill set, we can leverage decades of research on how to develop cognitive self-regulation, strategic thinking, and metacognitive awareness.

This calls for institutional commitment. Universities and K-12 schools should embed executive function development more prominently in their curricula—not as remedial support, but as foundational preparation for an AI-integrated world. These aren't just study skills; they're the cognitive architectures that enable effective human-AI collaboration.

Schools should consider:

Embedding EF instruction across disciplines rather than isolating it in special programs

Training faculty to recognize EF demands in AI-enhanced learning environments

Developing assessment frameworks that measure cognitive processes, not just technical outputs

Creating structured reflection practices around AI use that build metacognitive awareness

As I prepare for my talk at Ohio Wesleyan, I'm excited to explore how this executive functioning lens can complement and strengthen existing approaches to AI fluency education. Instead of viewing these as competing frameworks, we can integrate them to create more comprehensive, cognitively-grounded approaches to preparing students for an AI-augmented future.

I'm excited to learn alongside the educators, researchers, and students who will help build this bridge. The intersection of executive functioning and AI fluency isn't just an academic curiosity—it's the foundation of effective human-AI collaboration.

I need your help on this learning journey. If you have experience teaching executive functioning skills, assessing them, or connecting cognitive science to technology education, please share your insights in the comments. What methods have worked? What resources should I explore? What connections am I missing?

Speaking of putting these ideas into practice: I recently launched "The AI Driver's License for Faculty" - an online course that teaches educators how to maintain cognitive control when using AI tools. The "hands on the wheel" metaphor turns out to connect perfectly with executive functioning principles. If you are looking for a course that focuses specifically on this concept, check it out and let me know what you think.

I'm also excited to announce that we're expanding our team with three curriculum design specialists - Ned Courtemanche (History Department Chair at The McDonogh School), Wess Trabelsi (Technology Integration Specialist and AI/K12 Learning Consultant), and Matthew Karabinos (Middle Education Teacher and ASU/GSV AI Classroom Innovator). Together, we'll develop AI-integrated curricula that serves traditional educational goals while building the executive function skills students need for effective human-AI collaboration.