Grading the Chats: The Bad

The chat transcript brings you closer to the misconception

This is the second part of a series titled “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly” in which I analyze three different sets of student use of AI in project-based learning.

We are analyzing student interactions with Large Language Models on a holistic basis to create broad-based definitions and expectations of how we might like our students to communicate with an LLM. Think of these analyses as an effort to map the concept of responsible and effective use. Using an LLM means engaging in a conversation, not submitting a one-off request. We need to use principles of good writing and communication to teach effective use to our students.

So, we treat the LLM transcript like a piece of text that is worthy of analysis, just like any other, and apply our understanding of writing and communication to the dialogue between user and AI.

Remember, words are always words, whether they are being written by a robot or a human. If you can annotate and analyze a scientific article or a Hemingway short story, then you can annotate and analyze a chat transcript. You just have to come at it differently.

Context

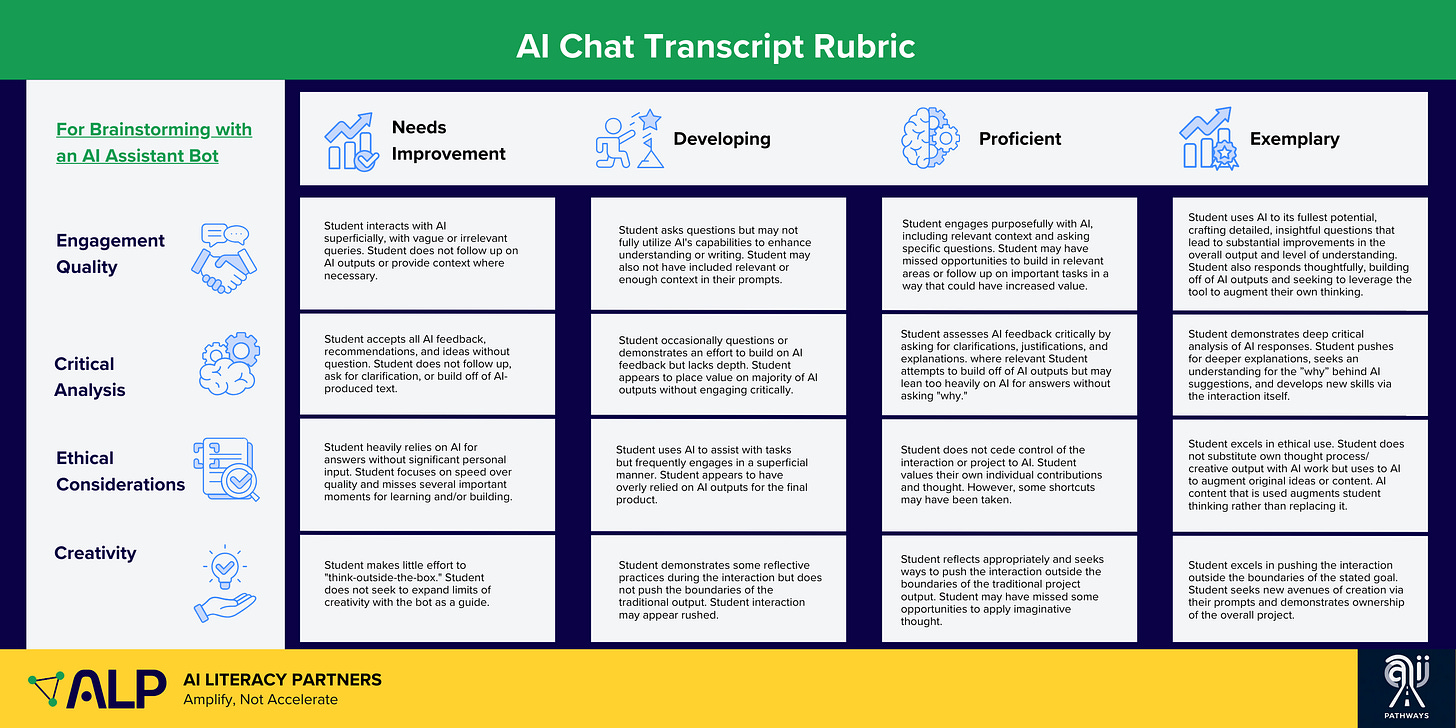

In the engagements you will see below, my students aimed to use ChatGPT as a brainstorm partner in a project-based learning exercise. I taught my students how to communicate effectively with Large Language Models, then gave them a practice run using ChatGPT as a brainstorm partner for a personal “bucket list” goal. They shared those interactions with me, and I provided written feedback.

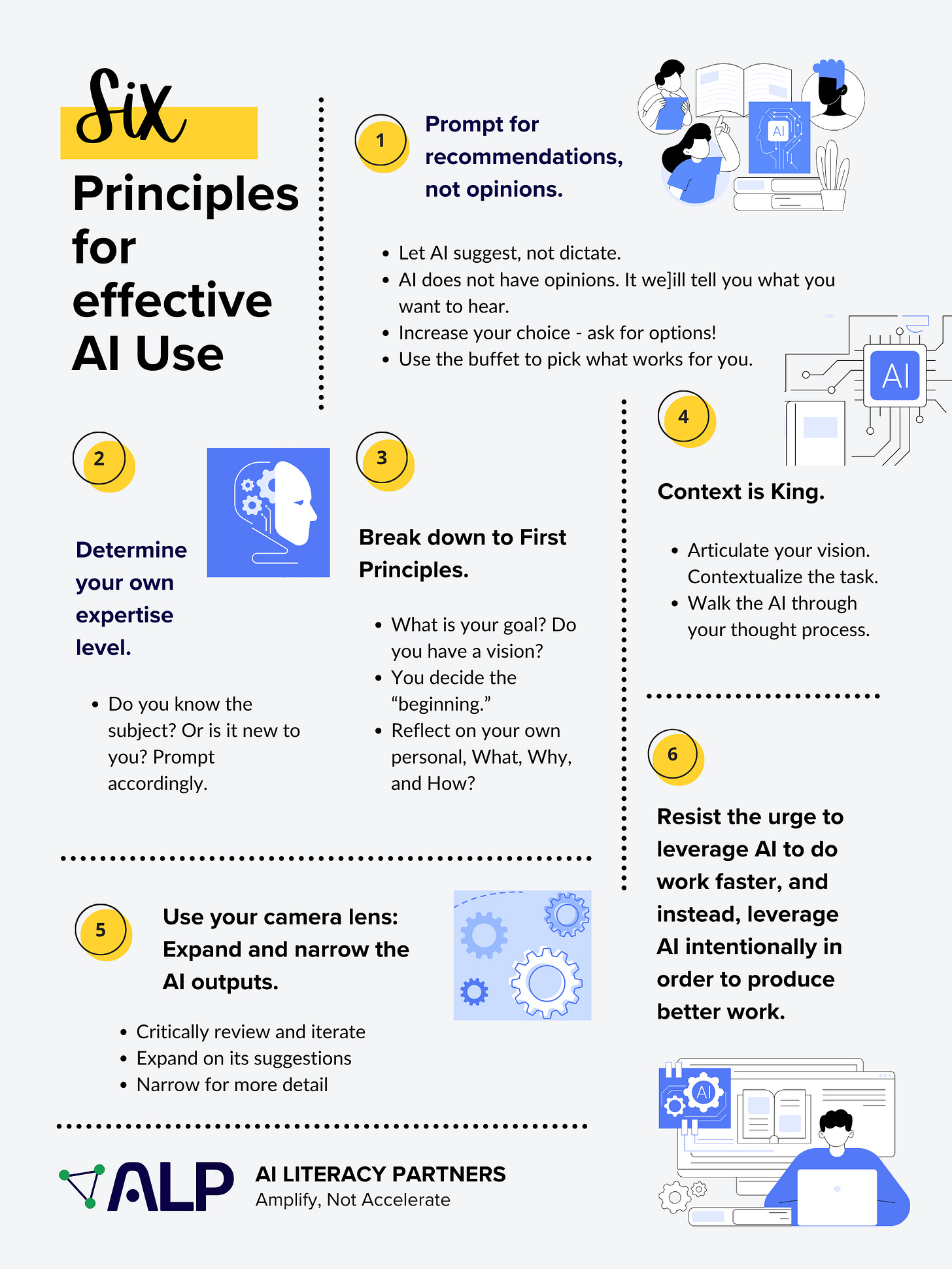

From these experiences and research, I composed the below set of “Principles for Effective AI Use” under the AI Literacy Partners banner. Feel free to analyze them and communicate your thoughts. I view this analysis as the first mile in a marathon, so I welcome constructive feedback.

Furthermore, feel free to use this infographic and the principles therein at your leisure, and let me know if you have feedback!

Without further ado, let’s take a look at ‘Angel Eyes,’ the ‘bad’ from “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.”

Yikes

If you read the first post in this series, you have all the context you need to consider what is going on here. If not, here’s the TLDR; this student chose to rewrite a scene from Romeo and Juliet in a different time period. I modeled the use of ChatGPT as a brainstorming partner using a method I created called Comparative Transcript Analysis. Then, I assigned the chat as a test. I told them I would be grading their ability to use the system thoughtfully based on my models and a co-constructed rubric.

Now let’s take a look at this again:

My first instinct was to label this laziness, and in truth that is part of the story. But upon closer inspection, there is actually quite a bit to unpack here.

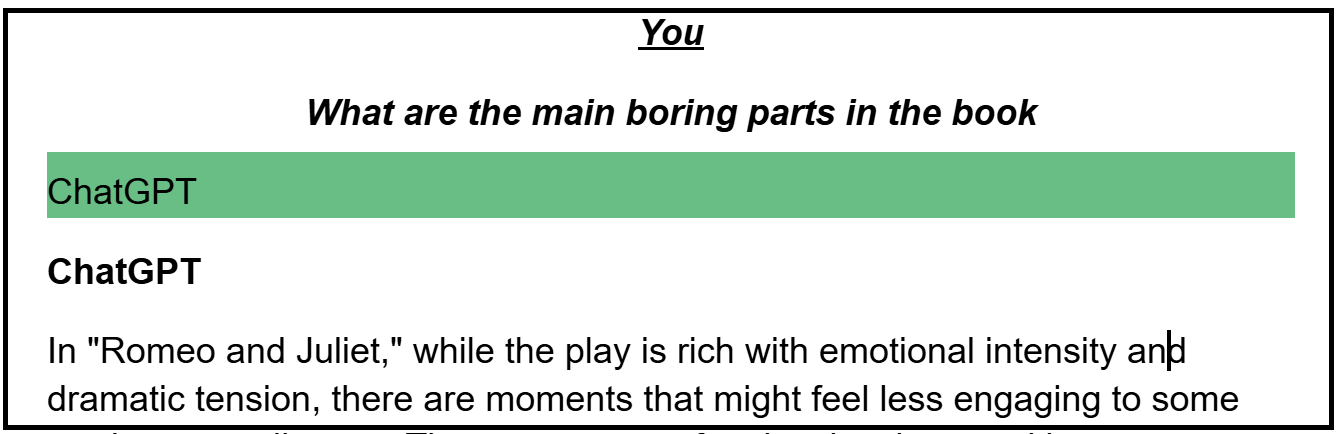

What is my student trying to achieve? If you closely read the project menu and try to trace this question to any of the objectives, you will find that it has no productive connection to any of the options, including but not limited to “re-writing a scene from the play in a different time period.” Boredom/entertainment level have nothing to do with that.

So, what gives? Where is this question coming from? What’s the misconception?

Here’s what I concluded: The “bad” of this prompt had nothing to do with this student’s writing or communication abilities. It had to do with his reading ability.

He didn’t read the project menu closely. He drew assumptions from skimming the menu that were not correlated with any of the final goals. As a result, his interaction with the LLM was (quite) poor. This is important to consider when grading the chat because a poor request or communication may not be a product of bad writing, an inability to communicate, or even laziness. It might simply be a product of a lack of close reading or clarity with regard to the objective.

However, on the writing side of the coin, this student did also violate one of our main core principles: Ask for suggestions and options, not answers or opinions. In this case, “boring” is a subjective opinion. There is no right answer to this question. He is asking the LLM to give him an answer that does not exist. He should be asking for suggestions, recommendations, or ideas - and I told him so!

The True Value of This Analysis

From this analysis, I was able to conclude two crucial facts about my student. One, he did not read the menu and/or clarify his overall purpose and goal before engaging. Two, he thinks that LLMs have opinions, which they don’t, and as a result handed over the keys to his learning journey to a robot.

Now, imagine that we did not have this process-based chat transcript to analyze our student’s thinking. The student’s final output — a re-written R&J scene — would likely have missed the mark by a lot (in fact, it did anyway). In that event though, we would be stuck trying to trace backwards from a bizarre output to an initial error early in the process - often a Herculean task for any educator.

By analyzing the process of thinking via the transcript, I was able to see the misconception at one of the earliest possible stages. It was much easier to trace back to his reading habits. This applies to the utilization of an LLM as a collaborator in any part of the project process, not just brainstorming. The chat transcript gets you closer to the core by opening a window into the process.

More Than Meets The Eye

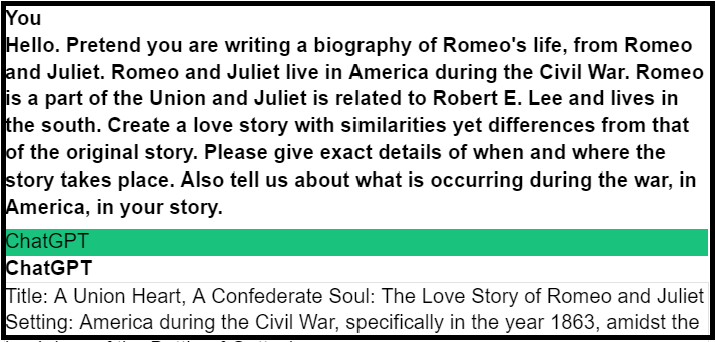

This student is trying to provide context, but the context does not follow in a logical manner. This one, unlike the other, is not a product of poor reading habits — in fact, I can see that he read my transcript fairly closely and made an effort to mimic it. However, his contextualization efforts actually amount to a version of bad writing.

Let’s walk through it.

First, in order to discern this error or misconception, I had to determine my student’s purpose or objective.

The student has already made up their mind regarding the broader reconstruction of the plot — they have decided to set their scene in the American Civil War, unlike the first student, who had not made a decision yet. In this case, my student used his own imagination to come up with an adapted storyline. That’s a good thing. Now he wants help figuring out the mechanics.

But in his subsequent prompt, he makes multiple broad requests, and it takes a minute to discern what he is really seeking. What does he actually want? It took me at least 3-4 reads to figure it out. From my view, his main request is for help in selecting and establishing a physical setting for his new story (the “when and where.”)

But then he tosses in a “tell us what is occurring during the war in your story.” At best this is a poorly delivered request - at worst it is borderline nonsensical - especially considering the fact that I hammered into them that AI does not “know” anything — ESPECIALLY when we are talking about a fictionalized story. Their language was meant to reflect that knowledge. More on that below.

But he also makes several small errors that show a lack of understanding. He calls it a “biography,” which it is not. He asks the AI to “pretend” when I modeled for them the practice of simply “telling AI who to be.” This is asking AI for an extra layer of metacognition it does not have — to “pretend” requires that I maintain grounding in who I really am, which in AI’s case, is nothing. Furthermore, the beauty of an LLM is that you don’t have to tell it to pretend because it is always pretending.

These are the types of snafus that tell me their understanding of what they are dealing with is minimal; and their understanding of the task itself appears to also be off-the-mark.

But forget prompt engineering for a second and just consider whether there is a clearer way to ask this question.

For example:

“I am going to rewrite Romeo and Juliet in the context of the American Civil War. Romeo is a member of the Union and Juliet is a member of the Confederacy. She is even related to Robert E. Lee. However, I cannot determine the best physical place and time period to set the story. When and where could my adaptation of Romeo and Juliet take place in order to heighten the tension while still following the general outline of the original plot?”

This question funnels from the broad to narrow - a la an Introduction Paragraph -- rather than haphazardly throwing context at the LLM while intermixing multiple requests. Whether or not this confuses the LLM is besides the point. The original version was simply bad writing and bad writing needs to be corrected. Remember, the point of “grading the chats” is not only to help your student learn how to use LLMs, but also to teach general effective communication in the context of a broader objective or learning experience.

Furthermore, my student asked ChatGPT for an answer, violating the core principles that tells users not to ask for answers or opinions. He wrote “Where should it take place?” There is no right answer to that question. In the context of working with LLMs, it is actually nonsensical. Instead, the revised prompt asks where the story could take place, which leads to an idea or suggestion.

This revised prompt also includes story-construction parameters to help the LLM land on a good suggestion. It asks, “Where could it take place in order to heighten the tension…?” In order to include that level of detail as the prompt writer, I had to actually think and decide what my goals were (or are) in the context of completing the project. This type of specificity would a) show an understanding of creative writing techniques, b) include a layer of specificity that would require critical thinking and reflection on the part of the student, and c) is much more answerable than the first version. It’s simply a better question. That’s not just an LLM skill, it’s a life skill.

Root Issue

Ultimately, this prompt failed because the student did not stop before writing and ask themselves “What am I trying to achieve?” or “What is my purpose?” If they were thoroughly clear on their desire for help with the setting, specifically, they could have pulled on that mental thread and written a better prompt, possibly even going deeper in connection with their goal.

In this case, unlike the first student, this student did read. They understood the overall objective and even engaged in some creative brainstorming before asking the LLM for help. But they lost connectivity to their own objective in the process of drafting a request for the LLM.

This is why the Purpose Statement is so important (Step 2). It is also why Larry Summers recently said that people who can define purpose and communicate effectively in groups (dialogue) will succeed in the future. It is also why Zainetek is built around the concept of protecting our ikigai — or soul’s purpose.

Conclusion

I did not ask my students to write a Purpose Statement for this project, so it is a bit unfair to criticize this student for forgetting his objective. The truth is, I was throwing spaghetti at the wall last February. But it was precisely from the process of grading their chats that I realized my students would need a Purpose Statement going forward.

I believe you will have similar a-ha moments if you try it yourself.

If you appreciate this work and want to see more, there are three things you can do:

Like this post.

Share this post.

Become a free or paid subscriber.

Writing these blogs takes time and effort, as you are well aware. All three of these actions provide the validation and support that I need to keep going. Any support you can provide is much appreciated.

Lastly, if you are a professor or teacher looking for a collaborative environment within which to design an assessment that allows you to “grade the chats” in the Fall, join our free CRAFT Program. Sign-up deadline is August 20th, 2024.

See you out there.

It is definitely true that students often don't know what their purpose is, which is the main reason their writing suffers ... whether its a prompt or an essay. I think structured prompting would come in handy here, because it would force students to identify their purpose and articulate it to the AI before they even describe the task!